History of Legal Attachés

History of Legal Attachés

|

|

| An FBI agent in Brazil uses a desktop lab to photograph documents. |

In 1940—a year before the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor pushed the U.S. into World War II—President Franklin D. Roosevelt realized that America needed more and better intelligence to understand the threats posed by the Axis powers.

The FBI was in charge of domestic intelligence, but there was no CIA at that time to handle overseas intelligence. Roosevelt decided to assign intelligence responsibilities for different parts of the globe to various agencies. The Bureau landed the area closest to home—the Western Hemisphere.

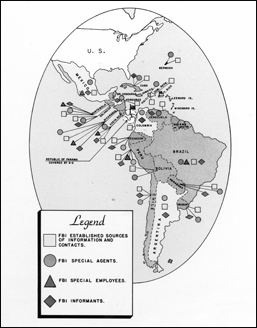

Strategically, it made sense—South and Central America were fast becoming staging grounds for the Nazis to send spies into the U.S. and hubs for relaying information back to Germany. In June 1940, the FBI responded to the president’s charge by setting up a Special Intelligence Service that deployed scores of undercover agents to ferret out Axis spy networks.

The FBI quickly realized that it needed to establish official liaison with the many countries it was working with across the world to coordinate international leads arising from the Bureau’s work and to exchange information with the police and intelligence services of those countries. In 1941, the U.S. Ambassador to Colombia requested the assignment of a special agent to the U.S. Embassy in Bogota. This proved to be the forerunner of the FBI’s legal attaché, or legat, program.

|

|||

| A map showing coverage provided by the Special Intelligence Service in the Western Hemisphere in 1941. | |||

By 1942, special agents were assigned to U.S. Embassies in London, Ottawa, and Mexico City, and they were carried on the Department of State’s diplomatic roster and given the title of “legal attaché.” The following year, a Liaison Section in the Security Division was established at FBI Headquarters to maintain contact with the legats, the State Department, the Armed Services, and other agencies.

As the need for intelligence related to the Axis threat in the West diminished towards the end of the war, the special agents assigned to posts in Europe, Canada, and Latin America began to make relationship-building and/or training their top priorities. In 1947, the FBI’s Special Intelligence Service was disbanded, and the newly formed CIA was tasked to take over foreign intelligence operations and to coordinate intelligence activities worldwide. But the Bureau’s network of Legats overseas had proven its worth and continued to crystallize its liaison mission.

The number of legats operating from the 1950s through the 1980s fluctuated greatly due to crime trends and budget allowances, with offices opening, closing, and reopening at various times. In the 1990s, FBI Director Louis Freeh—recognizing that global crime and terror were on the rise—made it a priority to open a series of new legal attaché offices. At the start of his tenure in 1993, the Bureau had 21 offices in U.S. Embassies worldwide; within eight years that number had doubled. Offices were opened, for example, in such strategic locations as Pakistan, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Turkey, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia.

That growth has continued. Today, the Bureau has special agents and support professionals in more than 80 overseas offices, pursuing terrorist, intelligence, and criminal threats with international dimensions in every part of the world. The FBI also takes part in all manner of global and regional crime-fighting initiatives, including Interpol and Europol, and Resolution 6, which co-locates FBI agents in DEA offices worldwide to combat drugs. It’s no exaggeration to say that the FBI is a global organization for a global age.

| International Links |

|

About Us Contact FBI Legats |