2005 Operations Report

|

2005 Operations Report Mission Statement To ensure national security and public safety by providing the timely determination of a person’s eligibility to possess firearms or explosives in accordance with federal law. In 2005, the FBI Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) Section, witnessed many significant improvements and achievements in the furtherance of its mission by identifying, developing, and implementing system improvements to consistently provide its users with a highly effective and efficient level of quality service. Highlights of the 2005 NICS accomplishments include the following:

Contents NICS 2005 Operations

NICS Enhancements

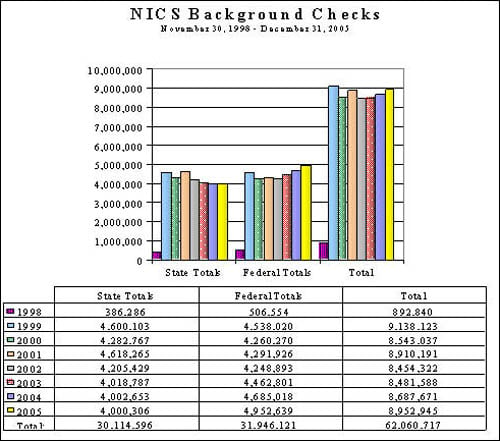

The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act (Brady Act) of 1993, Public Law 103-159, required the U.S. Attorney General to establish a National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) for Federal Firearms Licensees (FFLs)1 to contact by telephone, or other electronic means, for information to be supplied immediately on whether the transfer of a firearm would violate Section 922 (g) or (n) of Title 18, United States Code or state law. The Brady Act requires the system to assign a unique identification number (NICS transaction number [NTN]) to each transaction; to provide the FFL with the NTN; and to destroy all records in the system that result in an allowed transfer (other than the NTN and the date the NTN was created). Through a cooperative effort with agencies such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and the Department of Justice (DOJ), in addition to local and state law enforcement agencies, the FBI developed the NICS, which became operational on November 30, 1998. The NICS was designed to immediately respond to background check inquiries for prospective firearm transferees. For an FFL to initiate a NICS background check, the prospective firearm transferee must complete and sign an ATF Form 4473 which collects the prospective firearm transferee’s descriptive data and asks questions intended to capture information that may immediately indicate to an FFL that the subject is a prohibited person, thereby negating the need to continue the background check process. Pursuant to federal law, a prospective transferee is required to present proof of identity via a form of government-issued photo identification to an FFL prior to the FFL’s submission of subject descriptive data to the NICS. When an FFL initiates a NICS background check, a name and descriptor search is conducted to identify any matching records in three nationally held databases. These databases are: Interstate Identification Index (III): The III contains an expansive number of criminal history records. The III records searched by the NICS during a background check, as of December 31, 2005, numbered over 46,087,000. National Crime Information Center (NCIC): The NCIC contains information on protection orders, wanted persons, and others. The NCIC records searched by the NICS during a background check, as of December 31, 2005, numbered over 3,238,000. NICS Index: The NICS Index2 contains records contributed by local, state, and federal agencies pertaining to individuals federally prohibited the transfer of a firearm. The records maintained in the NICS Index, as of December 31, 2005, numbered over 3,960,000. Also, a fourth search, via the applicable databases of the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), may be required pursuant to federal law. In response to a mandate issued by the U.S. Attorney General in February 2002, a search of the ICE databases is conducted on all non-U.S. citizens attempting to receive firearms in the United States. In 2005, the FBI Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division’s NICS Section and its Point-of-Contact (POC) state counterparts requested over 30,600 such queries of the ICE. The 2005 number of Immigration Alien Queries (IAQ) requests represents an approximate 11 percent increase from the number requested in 2004. In the majority of cases, the results of background check inquiries provide definitive information explicating subject eligibility within seconds to minutes of the data entry of a prospective firearm transferee’s descriptive information into the NICS. A much smaller percentage of the inquiries are delayed due to missing or incomplete information, e.g., final dispositions or crime classification level, that is necessary in order to make a final determination as to whether the firearm transaction may be proceeded or must be denied. Currently, under federal law, the NICS cannot preclude the transfer of a firearm based on arrest information alone unless independent state law otherwise specifies; however, only a few states fall into this category. In instances where a valid matching record discloses potentially disqualifying record information (e.g., a felony offense arrest or a possible misdemeanor crime of domestic violence) that reflects missing or incomplete information, the NICS Section will search for the information needed to complete the record. This process often requires outreach to local, state, and federal agencies, such as court systems, law enforcement agencies, probation and parole agencies, etc. In these instances, the Brady Act provides three business days for the purpose of obtaining additional clarifying information with which to make a determination as to the prospective firearm transferee’s eligibility. If the information is not obtained within the three-business-day time frame and a final transaction status cannot be rendered, the FFL has the option to legally transfer the firearm; however, the FFL is not required to do so. Additionally, those individuals who believe they were wrongfully denied the transfer of a firearm based on a record returned in response to a NICS background check may submit a request to appeal their denial decision to the agency that conducted the check. The “denying agency” will be either the NICS Section or the local or state law enforcement agency serving as a POC for the NICS. However, in the event the “denying agency” is a POC state, the individual may elect, in the alternative, to direct their appeal request (in writing) to the NICS Section.3 The NICS Section created a Voluntary Appeal File (VAF) for the purpose of allowing lawful purchasers to request that the NICS retain information such as court documentation, arrest information, and fingerprint cards which may clarify or prove their identity to avoid erroneous delays or denials on future NICS transactions. The Safe Explosives Act requires that persons who transport, ship, cause to be transported, or receive explosives material in either intrastate or interstate commerce must first obtain a federal permit or license after undergoing a background check. Enacted in November 2002, as part of the Homeland Security Act, the Safe Explosives Act officially became effective on May 24, 2003. Background checks for explosives permits, under the Safe Explosives Act, are processed through the NICS by the NICS Section. Extensive measures are taken to ensure the security and the integrity of NICS information. Access to data in the NICS is restricted to agencies authorized by the FBI under DOJ regulations. The U.S. Attorney General’s regulations regarding the privacy and security of NICS information are available on the Internet. NICS Transactions Since the inception of the NICS and throughout the year ending on December 31, 2005, a total of 62,060,717 background check transactions were conducted through the nation’s firearms and explosives background check system. Of these transactions, 30,114,596 were processed through the POC states, while the majority, or 31,946,121 transactions were processed through the NICS Section (reference Figure 1).

Pursuant to the NICS Regulation, the FFLs will initiate background checks with the NICS by contacting either the NICS Section or a state-designated POC. Any state can implement its own Brady NICS Program by designating a local or state law enforcement authority within the state to serve as an intermediary between its FFLs and the NICS in a POC capacity. A state can, at any time, choose to become a POC state. A POC state can also, either through state law or by operation of state policy, cease operations as a POC state. The FFLs conducting business in those states that choose not to participate with the processing of NICS background checks will contact the FBI, via the NICS Section’s Contracted Call Centers, to initiate background checks (except where otherwise specified, e.g., a recheck following a successful appeal). As of December 31, 2005, the NICS Section provides full service to the FFLs conducting business in 29 states, 5 territories and 1 district, while 13 states have agencies acting on behalf of the NICS in a full-POC capacity by conducting all of their own state background checks via the NICS. Eight states continue to share responsibility with the NICS Section by acting as a partial POC. Partial-POC states have agencies designated to conduct background checks for handguns and/or handgun permits, while the NICS Section processes all of their long gun transactions. As a result of legislation passed on April 6, 2005, the state of Georgia ceased operations as a Full POC for the NICS effective July 1, 2005. As such, the NICS Section initiated a transition plan which included the enrollment of Georgia’s FFLs to conduct business with the NICS Section. The NICS Section received its first Georgia firearm check on June 20, 2005, via the NICS E-Check. As a result of Georgia’s change in NICS participation status, the NICS Section has assumed the processing of all background check inquiries submitted via Georgia’s FFLs. This change in participation marked the most recent of many state-initiated modifications to state participation with the NICS. Historical Changes in NICS State Participation as of December 31, 2005

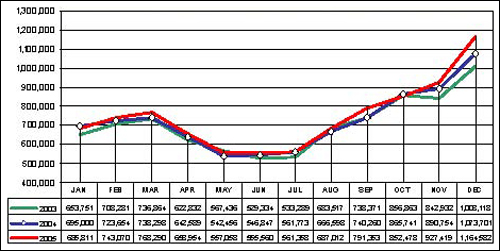

With the implementation of the NICS in 1998, certain state firearm permits (e.g., carry concealed weapon permits, permits to purchase) were qualified by the ATF as permits that would suffice in lieu of (e.g., an alternate to) a NICS check at the point of sale/transfer. As one of the requirements for eligibility to receive an ATF-approved alternate permit, a NICS background check must be included as part of the permit-issuing and renewal process. Alternate permits are issued for a designated period of time, many being valid for up to five years depending on the existing laws in the particular state of issuance. Presentation of an active alternate permit to an FFL when attempting to receive a firearm will preclude the necessity of the FFL conducting a NICS background check with each firearm transfer during the life of the permit. In 2005, as a result of the ATF’s comprehensive review of the in lieu of permit qualifications for each of the alternate permit states, several changes in participation occurred. As of December 31, 2005, there were 18 states and/or U.S. territories which were afforded alternate permit status by the ATF. The NICS Participation Map depicts those states which, as of December 31, 2005, maintained alternate permit status with the NICS. NICS Activity Yearly, the NICS experiences a consistent and predictable increase in transactional activity associated with the onset of state hunting seasons and the year-end holidays. Firearms are part of the retail industry; therefore, substantial increases in firearm sales historically begin in late summer and progressively increase through the month of December. Corresponding to the escalation in firearm sales typically witnessed in the months leading toward the end of a calendar year, the influx of transactional activity to the NICS also progressively increases. This period of time, when the number of firearm transactions are increasing (reference Figure 4), is referred to as the NICS “peak season.”

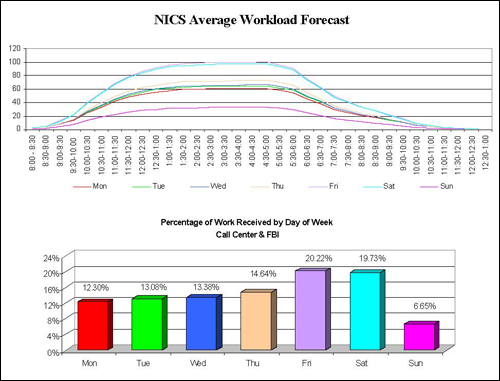

The NICS standard available hours of system operation are 8 a.m. EST to 1 a.m. EST, 364 days a year.4 However, in the spirit of effective and efficient customer service, and to accommodate the escalating transactional influx typically associated with each year’s “peak season,” the hours of system availability are customarily expanded to provide longer periods of access to the POCs. This additional available operating time aids in deterring potential “bottlenecks” which can accompany demand and activity levels associated with eminent “peak season” volumes. In order to successfully accommodate the increase of transactions during “peak season” and, in turn, provide optimal customer service to the NICS users in “peak” as well as “non-peak” times, the NICS Section allocates its resources by utilizing a workload forecast model. The NICS Section’s workload forecast model calculates and provides the data needed to determine the necessary adjustments to ensure adequate staffing for workload maintenance, both at the NICS Section and its Contracted Call Centers. The NICS Section’s staffing model, designed to calculate the number of NICS employees required for each business day, also evaluates current schedules to determine any anticipated or potential deficiencies. Similar to the retail industry, approximately 40 percent of all contacts are received on Friday and Saturday with the majority between the hours of 11 a.m. and 7 p.m. During anticipated times of greater demand, staffing levels are adjusted to support an increase in workload (reference Figure 5).

The NICS Section conducts ongoing comprehensive system and process checks aimed at assessing operational performance. Continual assessment of daily operations keeps the NICS Section current with ever-changing needs in order to maximize its resources to provide optimal customer service. The acquisition and installation of a supplemental software module in 2005 provides the NICS Section with an additional workload management tool via the utilization of advanced applications for various other aspects of business operations, e.g., projecting an effect on workload when unique and/or atypical impacts to daily business operations occur. The effective use and application of historical call volume, transaction volume, and time study data in predicting future workload requirements has enhanced the NICS Section’s ability to more effectively develop staffing projections and concise work schedules. This, in turn, continues to amplify the efficiency of workload management and provide consistent and optimal customer service to the users of the NICS. Since the implementation of the NICS on November 30, 1998, and through year-end 2005, a total of 473,433 firearm transactions (or approximately 1.48 percent) have been denied by the NICS Section. Until the passage of the NICS Final Rule on July 20, 20045, the POC states were not required to report final eligibility determinations (e.g., denials) to the NICS6; therefore, statistics outlining the number of background check denials rendered by the states is not available via the NICS. The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ (BJS) Firearm Inquiry Statistics Program, implemented in 1995, collects information on background checks conducted by local and state agencies. The local and state data, when combined with the NICS data, provide cumulative estimates of the total number of background check transactions and denials resulting from the Brady Act requirements and similar state laws. With data provided by the local and state agencies that conduct their own background checks, the BJS has estimated that approximately 507,167 local/state firearm transactions have been denied for the period of November 30, 1998, through December 31, 20047 (the 2005 data not available at this time). Referencing Table 1, the denial rates for the NICS Section (through December 31, 2005) as well as the states (through December 31, 2004) have steadily declined. Table 1 The NICS Denial Rate

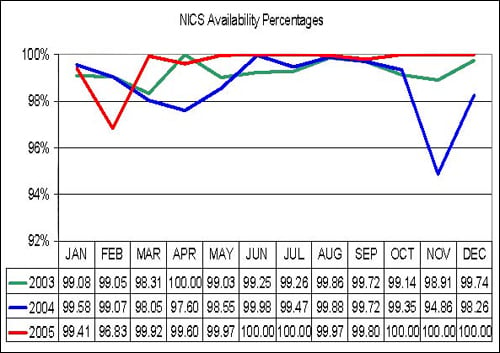

The leading reason for NICS Section denials, both historically and in 2005, is the existence of a felony record. Comparably, the BJS also reports that from 1999 through 2004 (2005 data unavailable), the majority of denials rendered by state and local agencies, parallel to the NICS Section, was the result of the applicants’ felony convictions or indictments. Federal Denials 473,433 as of December 31, 2005 When processing firearm background checks, if record-completing information (e.g., dispositions) is missing from a criminal history record and a final transaction decision of either proceed or deny cannot be determined and provided to the FFL within the Brady-mandated three-business-day time frame, it is the FFL’s option to legally transfer the firearm. In these instances, a firearm could be transferred to an individual who is later (e.g., after the subsequent receipt of disqualifying disposition information) determined to be a prohibited person. These types of scenarios are serious and require immediate attention by the NICS Section personnel and referrals to the ATF. The ATF determines if a firearm retrieval and/or a criminal investigation concerning the falsification of the ATF Firearm Transaction Form will be pursued. In 2005, the NICS Section referred 3,771 such scenarios to the ATF for further review, evaluation, and possible retrieval of the firearm and/or investigation. Since the implementation of the NICS in November 1998, and through December 31, 2005, records indicate that over 26,600 such transactions9 have been referred to the ATF for follow-up investigation. These types of situations present ongoing public safety and law enforcement safety risks as, in many instances, the firearm must be retrieved. While tremendous strides have been made by local, state, and federal agencies in availing record-completing/clarifying information to the law enforcement community, it is apparent that more is needed. System Availability of the NICS Providing optimal customer service is a key factor in the success of any organization or program; therefore, maintaining a high level of system availability and accessibility remains a top priority for the NICS Section. Partnering with the NICS to provide information necessary in the background check process, the CJIS Division manages the operations and maintenance of the NICS’ interfacing systems that collectively are termed the CJIS System of Services (SoS). The CJIS SoS, comprised of the NCIC, the NICS, and the Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System, provides fingerprint identification capabilities, criminal history services, wanted person checks, etc. The information available through the CJIS SoS facilitates law enforcement operations and various public safety initiatives across the United States and additionally provides the information needed to determine subject eligibility for individuals attempting to receive firearms or firearms/explosives permits. As such, the NICS is dependent on the information provided by the CJIS SoS in order to operate as designed and to complete each query of the system in an efficient and effective manner. Prior to 2005, the CJIS Division implemented and successfully completed a “rehost” of the systems comprising the SoS (the NICS’ partnering systems) to a newer state-of-the-art “superdome” environment. After a great deal of planning and preparation by the staff of the NICS Section and the CJIS Division’s Information Technology Management Section (ITMS), the relocation of the NICS, as the final phase of the CJIS Division’s overall rehost project, was successfully accomplished on April 10, 2005. In today’s business world, all organizations strive to achieve a 100 percent service availability level. Whatever the service or the product, good service champions good business. As such, the relocation of the NICS to a more sophisticated infrastructure housing all of the systems comprising the CJIS SoS launched a more robust partnership between the systems searched during the background check process. The movement of the CJIS SoS to its new operating platform successfully enhanced the overall effectiveness and efficiency of the CJIS Division Systems including the NICS (reference Figure 7).

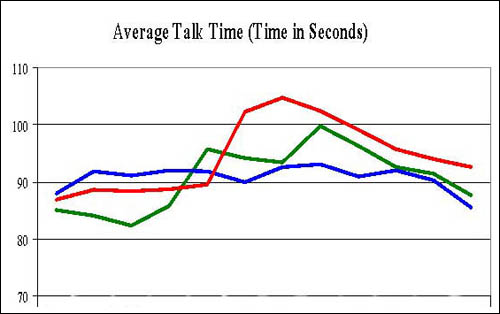

With the rehost of the NICS to the CJIS SoS, dramatic strides in the NICS availability level were witnessed in 2005. Prior to 2005, a 100 percent NICS availability level had only been noted once, in April 2003. After the implementation of CJIS Division technological advancements, the NICS witnessed five months of 100 percent system availability and noted a total yearly availability average of approximately 99.63 percent during 2005. The NICS background check process requires the application of several interconnected but separate and distinct operating systems and corresponding processes to achieve its stated purpose. Issues with service availability have been greatly depreciated; however, even with intermittent periods of service unavailability, the quality of service provided to the NICS customers remains outstanding. Performance measures are used to assess an organization’s progress relative to the implementation of business policies, strategies, and activities. Providing indications of an organization’s ability to efficiently and effectively avail its product or service, performance measures supply an organization with the necessary tools utilized in measuring the quality of their output. By defining specific and critical measurable elements, a business can assess how various attributes which cumulatively comprise daily business operations have performed. The performance of these identified elements guide an organization to success by providing an overview of business variables that assist management in identifying opportunities for program enhancement and sustainable changes that will contribute to tangible improvements. Notwithstanding intermittent issues that occur with interfacing CJIS Division Systems or periodic spikes in the transactional influx of incoming background check inquiries which can occur for a number of reasons (e.g., world or U.S. current events, legislative changes, etc.), the NICS Section continues to exceed performance expectations and remain consistent in providing exceptional service to its users. • NICS Section’s Average Talk Time: The NICS Section’s average talk time during the Transfer Process refers to the amount of time spent on providing service from the time the call is answered until the call is concluded. The mission of the NICS Section is to provide the timely determination of a person’s eligibility to possess firearms or explosives in accordance with federal law. With this philosophy in mind, a timely determination requires minimal time spent in completing a background check during the FFL’s initial telephone call. Based on various factors, e.g., historical call averages, and absent a comparable industry standard, the NICS Section established a target average talk time of less than 95 seconds. In 2005, the NICS Transfer Process and Customer Service processes were combined as one functionality. This realignment witnessed some elevation in the talk-time level until necessary adjustments in the reporting calculations were effected. Overall, the NICS Section’s Transfer Process talk time for 2005 averaged at approximately 94 seconds for the year, thereby continuing to meet or exceed the Section’s internally established goal (reference Figure 8).

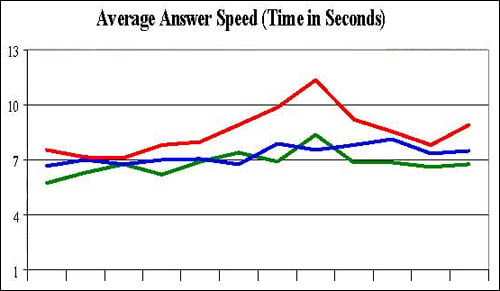

• NICS Section’s Average Answer Speed: The NICS Section’s answer speed during the Transfer Process refers to the average amount of time (calculated in seconds) that a caller waits before the call is answered by a NICS Section employee. Many factors, such as the time of the day, week, month, year, etc.; changes in processes; system and/or technological modifications; and increases in product demand can have a bearing on the rate at which calls are addressed and processed by the NICS Section. Additionally, higher transactional levels, e.g., those associated with the NICS “peak season,” place a greater demand on the system which, in turn, can affect various service levels. Similar industry standards (e.g., similar to those for call centers) assess an average answer speed at approximately 80 percent of all calls being answered within 20 seconds; however, the NICS Section strives to achieve better and has established an internal processing goal of all calls being answered within seven seconds. In August 2005, the NICS Section adjusted its average answer speed goal from seven to nine seconds due to the implementation of Whisper Technology10 which added approximately two additional seconds to the Transfer Process answer speed rate. As such, the NICS Section’s answer speed rate for 2005 (reference Figure 9) averaged approximately nine seconds and again meeting its internally established goal and surpassing industry standards.

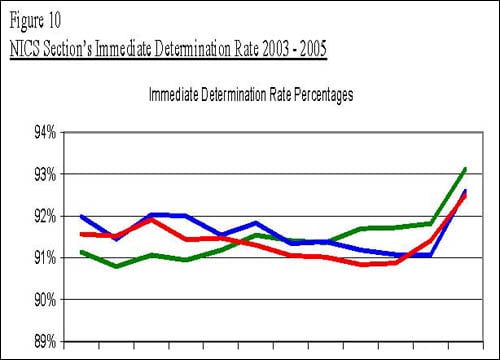

• NICS Section’s Immediate Determination Rate (IDR): The NICS was established so that any FFL can contact the system, via the NICS Section or a state-designated POC, for information to be supplied immediately as to whether the transfer of a firearm would be in violation of federal or state law. Cognizant of its mission, the NICS Section continually strives, via enhanced methods and system upgrades, to improve the rate by which the subjects of background check transactions can receive an immediate response as to subject eligibility. In 2002, pursuant to a directive by the U.S. Attorney General, the NICS Section identified, developed (with the assistance of the CJIS Division’s technical support staff), and ultimately implemented the “Transfer Process” as a means to increase the NICS Section’s IDR, the rate by which final transaction statuses are provided to the NICS Section’s customers during the FFL’s initial call initiating a firearm background check. As a result of the deployment of the NICS Section’s Transfer Process, in July 2002, a dramatic increase in the IDR was realized. Even with an almost 6 percent increase in the number of transactions received by the NICS Section for processing in 2005, the IDR remained consistent at 91.47 percent for 2005 (reference Figure 10).

The NICS Section recognizes that the continued success of any organization depends on a good working relationship between the independent components that cumulatively comprise its overall operations. In order to conform with evolving business and operational needs, and to repeatedly meet or exceed continued excellence in service, the NICS Section consistently works to identify and develop upgrades and system enhancements to ensure the continued success and viability of the NICS. In order to remain one step ahead of ever-changing technology and business needs, the NICS Section must continually enhance the NICS to meet the demands placed upon the nation’s firearms and explosives background check system. Some of the upgrades and/or enhancements effected by the NICS Section and the ITMS in 2005 are: NICS Rehost On April 10, 2005, the NICS was relocated from its previous multi-platform architecture to that of a single vendor “superdome” environment. The relocation of the NICS, the latest in a series of rehosts of the CJIS Division Systems from an older, unsupported architecture to that of a fully supported “state-of-the art” superdome environment, was completed as scheduled and without incident. The rehost of the NICS marked the successful completion of the CJIS Division’s overall rehost project. The integration of the NICS within the same operating platform as that of the III (in addition to other CJIS Division Systems) has created a more robust partnership between all the systems collectively referred to as the SoS and further enhanced the overall effectiveness and efficiency of the NICS as witnessed by the increased system availability level reported in 2005.11 Workload Management Technology In January 2005, the NICS Section implemented the utilization of a new workload scheduling software package. The new workload scheduling tool provides the NICS Section with the capability to better manage employee work times and workloads. Using specific types of data, such as historical call and transaction volumes, the scheduling software is designed to more effectively generate forecasts of anticipated contact volumes. The implementation and application of the aforementioned software has greatly assisted the NICS Section in creating detailed work schedules to ensure that the level of required employees with the skill sets needed to meet the needs of the NICS customers is parallel to the level of available staffing. (For additional information, reference page 8.) The NICS Section is currently utilizing Whisper Technology, a software package that generates an automatic telephonic announcement specifying the type of incoming call (either Transfer Process or Customer Service) that a NICS Legal Instruments Examiner (NICS Examiner) is about to receive for processing. Whisper Technology has allowed the NICS Section to effectively combine the previously separate Customer Service and Transfer Process functions into one single function, thereby increasing the efficiency of the NICS Examiners via multitasking capabilities. Each specific type of function requires different types of information retrieval and processing. By providing an audible introduction of the type of call pending, the NICS Examiners are able to prepare for the type of processing required to effectively and efficiently facilitate each call received. The NICS Section deployed Whisper Technology in June 2005. Firearm Retrieval Referral Codes In response to a recommendation by the DOJ’s Office of the Inspector General in a report entitled, “Review of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Enforcement of the Brady Act Violations Identified Through the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, Report Number 1-2004-006,” the NICS Section initiated the development of a system change to enhance the timely facilitation of firearm retrieval cases referred to the ATF for investigation and/or prosecution. To assist the ATF with workload management and prioritization, the NICS Section implemented a system enhancement that (1) ranks a delayed denial transaction based on ATF-determined categories applicable to the specific denial, and (2) separates the ranked delayed denials from the standard denials, thereby allowing the ATF to identify and/or prioritize referrals where a firearm must be retrieved. This initiative was successfully implemented by the NICS Section on July 17, 2005. NICS VAF Access via CJIS Internet Local Area Network (LAN) To enhance existing services, the NICS Section identified a means that would allow for the secure access of the VAF by the POC states. By charting the identifying and record information of successful VAF candidates into a standard text file format, e.g., by Unique Personal Identification Number (UPIN) and/or alphabetically by last name, the NICS state counterparts, as of February 9, 2005, are capable of accessing the information maintained in the VAF database via the CJIS Internet LAN (formerly known as Law Enforcement Online). To provide the NICS Section employees with all the tools necessary to perform their assigned duties within the confines of their individual workstation in an efficient and effective manner, the NICS Efficiency Upgrade Project was envisioned. With development underway in 2003 and 2004, Phase I-A of the project, entitled PC Client, was deployed by the NICS Section in June 2005. PC Client provides the NICS employees with a single point of access to the databases necessary to process NICS background check transactions at their workstation. The PC Client functionality provides desktop accessibility to the national databases searched by the NICS during the background process without the employees having to leave their desktop workstation. In November 2005, the NICS Section initiated the implementation of Phase I-B of PC Client by adding two features to its work environment—the outbound facsimile server and internal e-mail capability. The outbound facsimile server provides NICS Section employees the capability to send facsimile requests/messages to external agencies from their desktop within their individual workstation. This functionality alone has proved beneficial to the NICS Section as employees no longer have to expend time by leaving their desks to transmit facsimiles to outside agencies. Additionally, the internal e-mail option allows the NICS Section employees to send electronic mail to all levels of responsibility, thereby enhancing the timely facilitation of internal communications. The completion of Phase II of PC Client is scheduled for July 2006. Currently in development for the future deployment is:

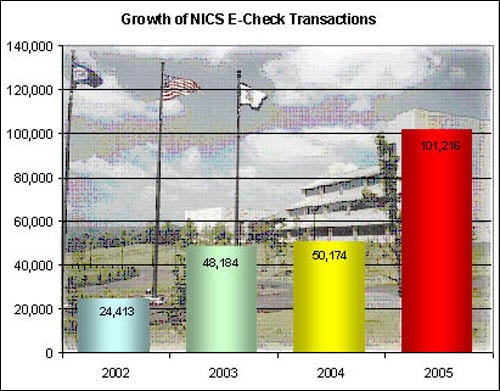

The NICS E-Check provides the FFLs with the capability to initiate an unassisted NICS background check for firearm transfers via the Internet. In the alternative, the FFLs utilizing the NICS E-Check also maintain the capability to initiate background checks telephonically via the NICS Section’s Contracted Call Centers. From the implementation of the NICS E-Check in August 2002, through December 31, 2005, approximately 223,987 transactions have been conducted via the Internet-based electronic access to the NICS (reference Figure 11). In 2005, the NICS E-Check transactions increased approximately 100 percent over 2004. As of December 31, 2005, there were approximately 2,026 FFLs actively enrolled with the NICS E-Check.

Utilizing the NICS E-Check, an FFL performs direct data entry of a prospective firearm transferee’s descriptive information into the system rather than relay the data telephonically to a contracted Call Center employee, thereby increasing data integrity and, ultimately, producing more effective search results. Additional benefits of using the NICS E-Check12 are:

Further initiatives regarding the NICS E-Check were identified and implemented in 2005 Implemented Modifications to the NICS E-Check

Initiatives in Progress for the NICS E-Check

bottlenecks can occur within the public telephone network. Such scenarios could limit a state’s capability of providing effective and efficient customer service. Currently, most firearm transactions initiated through a state POC require operator intervention. The implementation of the NICS E-Check functionality for the POC states would provide an optional process for implementing background checks that could alleviate some of the operator delays encountered when facilitating the background check process at the state level. As of December 31, 2005, the NICS E-Check enhancement to provide access for FFLs operating in the POC states continued in development. The NICS Section anticipates the implementation of a pilot operation to test the aforementioned enhancement to the NICS E-Check in September 2006. VAF Per Title 28, C.F.R., Part 25.9(b)(1), (2) and (3), the NICS Section is mandated to destroy all identifying information submitted by or on behalf of any person who has been determined not to be prohibited from possessing or receiving a firearm within 24 hours of the FFL being notified. On July 20, 2004, pursuant to the NICS Final Rule13, the NICS Section implemented the VAF, a database that maintains specific information (e.g., fingerprint cards, documentation) voluntarily provided by applicants for use in determining their eligibility to receive firearms associated with future background checks. The VAF, which is accessed and searched during the background check process, aids in preventing extended delays and erroneous denials for successful applicants. As a result, lawful purchasers who have been delayed or denied a firearm transfer because they have a name or date of birth similar to that of a prohibited person (or other such scenarios) may also request that the NICS maintain information about them to aid in facilitating future firearms transactions. The VAF is a paper file containing documentation submitted by the applicant and any documentation discovered during research that assists the NICS Section in justifying the individual’s inclusion into the VAF. The VAF is also an electronic file containing descriptive information from the paper background checks conducted by the NICS Section as well as the POC states. The information in the VAF will prevent lawful potential firearm purchasers from filing numerous appeal requests and resubmitting supporting documentation, fingerprints, and/or information that would allow a proceed transaction. The successful entry in the VAF of lawful firearm purchasers will decrease the amount of time needed to process approved transactions. Approval for entry into the VAF includes, but is not limited to, the following:

When a subject is deemed eligible for entry into the VAF, a UPIN is assigned and the entry is placed into an “active” status. The subject is instructed to provide the UPIN to the FFL whenever attempting to purchase or redeem a firearm. The information kept in the VAF will provide the NICS Section with positive proof of the subject’s identity, allowing the lawful transfer of a firearm to take place. An applicant may be disqualified for entry into the VAF for various reasons, e.g., a prohibitive record exists, insufficient information, and others. Under this process, potential purchasers may apply to be considered for entry into the VAF by signing an applicant statement which authorizes the NICS Section to retain information that would otherwise be destroyed. A complete NICS check is still required for future purchases by the applicant and will result in a denial if additional prohibitive information is discovered. The NICS Section is required to destroy any records submitted to the VAF upon written request of the individual. Since the VAF began processing cases in July 2004, a total of 297 successful VAF checks have been conducted (reference Table 2). These participants were able to purchase a firearm from a gun dealer without experiencing a lengthy delay or denial. Table 2 VAF Statistics from July 20, 2004, through December 31, 2005

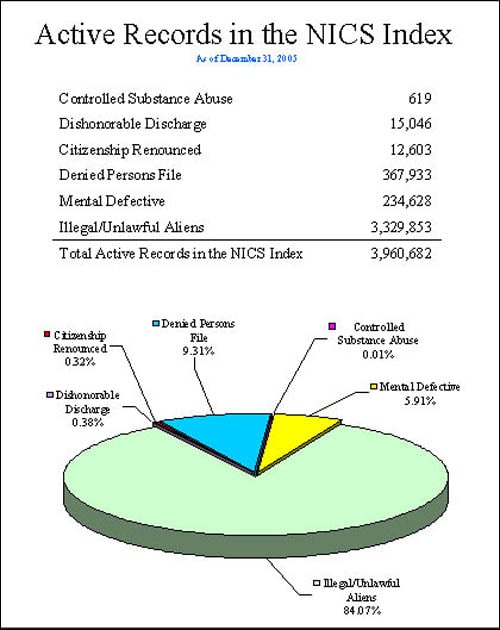

* Background checks subsequently conducted for VAF applicants after being successfully entered into the VAF database. Pursuant to 28 C.F.R., Part 25, the NICS Index database was created specifically for use by the NICS and contains records that are not maintained in either the III or the NCIC database, obtained from local, state, and federal agencies pertaining to persons federally prohibited from receiving firearms. All records in the NICS Index will immediately prohibit the individual record holder from the transfer of a firearm. Records are entered into the NICS Index and maintained via one of several specific and distinctly outlined files. The Federal Register (Volume 62, No. 124) identifies the various types of entries by specific categories. The categories within the NICS Index are outlined as follows:

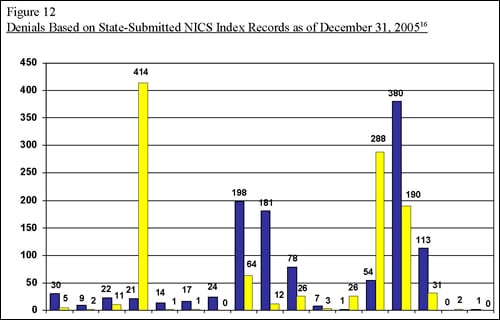

To increase the quantity of available records for inclusion in the NICS Index, the NICS Section initiated an outreach program15 to connect with the law enforcement and judicial community, various state and federal agencies, and the general public and to boost awareness of the availability and benefits of the NICS Index. As a result of numerous efforts by the NICS Section, the number of records contained within the NICS Index has witnessed exceptional growth since program implementation. In 2005, an additional 295,835 records were contributed to the NICS Index and from program inception through December 31, 2005, the NICS Section succeeded in increasing the number of available records in the NICS Index by approximately 325 percent. The NICS Index is a valuable tool in providing immediate accessibility to federally prohibitive records (e.g., disqualifying mental health records) previously unavailable at the national level. The submission of disqualifying records by state agencies has proven to have a positive impact to public safety by providing information accessible to all users when performing NICS background checks. Without this information being readily available, prohibited persons may be successful in their attempts to receive firearms merely by crossing state lines. Referencing Figure 12, it is apparent that the availability of state-held information on a national level has a tremendous impact on public safety.

The following story is an example of how the unavailability of prohibiting records at the national level can lead to tragic results: A 44-year-old man was charged with the murder of his 32-year-old ex-girlfriend, shot to death at her place of employment. Reportedly, the alleged gunman walked into the business via the back door and fired several shots with a handgun. The alleged gunman’s attorney acknowledged that his client committed the crime but emphasized his prior history of mental illness. The alleged gunman was institutionalized and treated for depression and other mental health illnesses as early as age 12 and also had a history of substance abuse. None of the mental health records were in the NICS Index for accessibility during the background check process. Had the records explicating the aforementioned individual’s prior mental health history been made available via the NICS Index, the aforementioned tragedy may not have occurred. As with every other facet of program operations, the NICS Section remains proactive in seeking vital record information necessary to effectively facilitate the nation’s firearms (and firearms/explosives permits) background check program. As of December 31, 2005, approximately 24 states were submitting or had contributed records to the NICS Index (some on a limited basis) and the NICS Section was in contact with several states to solicit vital record information for the NICS Index. By obtaining and availing decision-making information (especially records not accessible through the NCIC or the III databases) to the users of the NICS, all states will have access to valuable prohibiting records when performing a NICS background check. Figure 14 reflects the number of active records in the NICS Index per category, as of December 31, 2005.

Violent Gang and Terrorist Organization File (VGTOF) Processing During the background check process, the NICS searches the III, the NICS Index and the following specific files maintained and availed by the NCIC: the Foreign Fugitive File; the Immigration Violator File; the Protection Order File; the Wanted Person File; the U.S. Secret Service Protection File; the Sentry File; the Convicted Persons on Supervised Release File; the Convicted Sexual Offender Registry; the Gang/Terrorist Organization File; and the Gang/ Terrorist Members File. In February 2004, the latter two files were added to the NCIC files searched during a NICS background check, as a result of a November 2003 DOJ directive. Pursuant to the November 2003 directive, the processing agency (either the NICS Section or a POC) is required to delay transactions that generate matches to the VGTOF (a collective term for both the NCIC’s Gang/Terrorist Organization File and the Gang/Terrorist Member File) for manual review and evaluation. NICS personnel can then coordinate with FBI field agents to determine whether the agents have prohibiting information about a prospective purchaser on the watch list that is not yet available in the automated databases checked by the NICS. Persons whose record information is maintained in the VGTOF are not specifically prohibited from possessing or receiving firearms unless one or more of the federal firearm prohibitors, pursuant to the Brady Act, exist. With the assistance of the Terrorist Screening Center (TSC), a determination is made as to the validity of the descriptive record match. If determined a valid match, the TSC will refer the NICS VGTOF Examiner to the Terrorist Screening Operations Unit and/or the Counterterrorism Watch. The NICS VGTOF Examiner advises of a match and solicits for any information that could prohibit the individual from receiving a firearm pursuant to state or federal guidelines. Prior to July 17, 2005, the POC states processed their own NICS VGTOF transactions for background checks; however, as a result of a 2004 audit conducted by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), it was determined that inconsistencies, e.g., procedural interpretations or standards of operation, existed in the implementation of VGTOF hit protocols by the POC states as compared to the NICS Section. In response to this finding, the Department determined the volume of VGTOF transactions processed by the POC states was low enough to allow all of the NICS VGTOF transactions (state and federal) to be effectively and efficiently processed via the NICS Section. Doing so would relieve the states of the responsibility of ensuring overall consistency in processing all VGTOF-matched transactions. Accordingly, the NICS was enhanced to provide an automated message to the POC states that when the NICS generates a response that includes a VGTOF-matched record, no final determination should be made regarding the transaction until further notification is received from the NICS Section. This change in procedure provided a resolution to the inconsistencies found during the GAO audit. As such, on July 17, 2005, the NICS Section began processing all VGTOF transactions including those from POC states. In 2005, the NICS Section processed 239 valid VGTOF matches based on descriptive information. A total of 19 of the valid VGTOF matches processed by the NICS Section resulted in denials. All of these denials were based on information maintained in the databases searched by the NICS or obtained through routine research typically associated with processing background checks, e.g., missing dispositions, as opposed to information obtained from inquiries made of field agents. NICS Appeal Services Team (AST) The NICS Section is committed to ensuring the timely transfer of firearms to law-abiding citizens while denying transfers to persons who are specifically prohibited by law from receiving or possessing firearms. As provided in the permanent provisions of the Brady Act and further outlined in the NICS Regulations, 28 C.F.R., Part 25.10, individuals who, as a result of the NICS background check, believe they were wrongfully denied the transfer of a firearm may submit a written request for an appeal of that decision. Table 3 Historical NICS Section Appeal Statistics

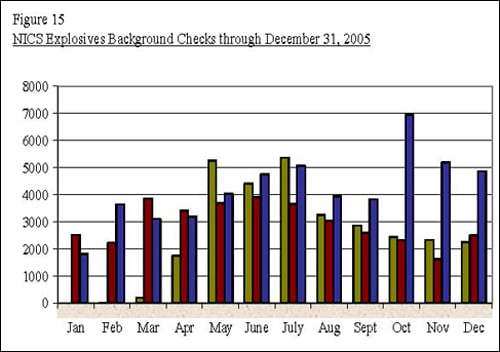

(Based on NICS Section Statistics only) Explosives As of November 25, 2002, and pursuant to the Safe Explosives Act, enacted as part of the Homeland Security Act, any person who transports, ships, causes to be transported, or receives explosives materials in either interstate or intrastate commerce must obtain a federal permit or license issued by the ATF after undergoing a background check. The Safe Explosives Act requires that background checks be conducted on two separate categories for licenses, responsible persons and employee possessors, and one category for permits, a “limited” permit. A responsible person is an individual who has the power to direct the management and policies pertaining to explosives materials (e.g., sole proprietors, explosives facility site managers, corporate directors and officers) as well as corporate stockholders who have the authority to direct management and policies. An employee possessor is an employee authorized by a responsible person to possess explosives materials and is defined as an individual who has actual physical possession or constructive possession, meaning the individual has dominion or direct control, over the explosives materials. This category includes employees who handle explosives materials as part of the production process (e.g., shipping, transporting, or selling of explosives materials) and employees who actually use the explosives materials. Responsible persons and employee possessors must submit an application to include identifying information and fingerprints to the ATF National Licensing Center (NLC) which, in turn, submits the information directly to the CJIS Division where identification processing is effected. Once the identification processing is completed, the data is electronically forwarded to the NICS Section where a background check will be conducted with results returned to the ATF NLC via the NICS E-Check. A limited permit is designed for the intrastate purchaser who buys explosives infrequently and does not intend to transport or use the explosives interstate, e.g., farmers or construction companies that acquire or use explosives infrequently within their own state of residence. The permit is valid for one year, is renewable, and will allow the purchaser to receive explosives materials from an in-state explosives licensee no more than six occasions during their permit’s life. The ATF NLC retrieves the results via the NICS E-Check. The most notable differences between processing a firearms background check versus processing an explosives background check is the fact that misdemeanor crimes of domestic violence and domestic violence restraining orders are not prohibitive categories for explosives background checks. In 2005, the NICS Section processed a total of 50,417 explosives background checks (Figure 15). Of the explosives background checks processed by the NICS Section in 2005, a total of 6,755 transactions were processed for responsible persons, and a total of 43,662 background checks were submitted for employee possessors.

Note: Gold is 2003, Red is 2004, and Blue is 2005. In August 2004, a task force was implemented for the purpose of the review and evaluation of the many recommendations proffered by the NICS Section’s employees in the furtherance of the streamlining and enhancement of the NICS Section’s work processes. In order to maximize the use of all available resources, the mission of the NICS Streamlining Initiative—to identify, research and evaluate all recommendations for the improvement and enhancement of the NICS for feasibility, added value to the program, potential cost and/or time savings, and improvements to the overall program efficiency and effectiveness—has been incorporated as part of the NICS Section’s standard operating processes. Some of the more significant changes implemented in 2005 are:

The NICS Section’s Outreach and Information-Sharing Program One of the biggest challenges facing public safety and law enforcement agencies today focuses on the manageability and need for complete and accurate record information. The inability of many law enforcement and judicial agencies to receive accurate and complete information easily and effectively impedes criminal justice efforts in many ways and at many levels. Optimal available record information not only helps to avoid tragedy resulting via criminal activity but also aids in solving crimes; trending crime patterns; providing opportunities to develop and effect public, victim, and officer safety planning initiatives; and offers guidance in determining possible alternative solutions or plans to mitigate the potential for future crime. In today’s society, America is witnessing a dramatic increase in the use of criminal record background checks to determine where individuals can work, volunteer, engage in various activities, etc., in addition to determining subject eligibility to obtain firearms and/or firearms and explosives permits. As such, the NICS Section’s quest for optimally available and accurate criminal history records (CHR) only continues to gain significance. Accurate firearms and explosives eligibility decisions, determined by the NICS, are contingent on:

The unavailability of relevant subject-disqualifying information to the national databases searched by the NICS does present real and serious public safety issues. For instance, if the NICS Section cannot make a determination regarding a person’s firearms eligibility based on incomplete information matched by the system, federal law provides three business days with which to conduct research in order to determine either a proceed or a deny decision. If the record information needed to effect a final transaction status cannot be obtained and a final transaction decision rendered within the three-business-day time frame, the FFL can legally transfer the firearm. This presents the potential for a firearm to be transferred to an individual who is later determined to be a prohibited person. In these instances, a firearm retrieval referral is sent to the ATF. The NICS Section remains committed to its mission, “To ensure national security and public safety by providing the timely determination of a person’s eligibility to possess firearms or explosives in accordance with federal law.” As such, just as important to block the transfer of a firearm (or firearm/explosives permit) to an individual disqualified pursuant to state and/or federal law, missing or unavailable record information also hinders the NICS Section’s ability to approve a background check transaction for a person who is not prohibited. In certain instances, lawful purchasers are denied or are subject to lengthy delays because of incomplete and/or unavailable record information. In an attempt to mitigate the aforementioned stumbling blocks to optimal effective and efficient background check processing, the NICS Section, shortly after program implementation in 1998, initiated an outreach and information-sharing program with the law enforcement and judicial community, in addition to the general public. The focus of the NICS Section’s outreach and information-sharing efforts remains intrinsic to the goals and objectives of the NICS Section and the ultimate benefits to be achieved via a coordination of efforts by all in the law enforcement and judicial community in providing complete and available criminal history (and related) record information. The following information depicts some of the specific initiatives implemented: With the aforementioned philosophy in mind, the NICS Section established the NICS Travel Team. The mission of the NICS Travel Team is basic—to travel across the United States (and territories) for the fundamental purpose of educating law enforcement and judicial agencies, among others, about the NICS program and the benefits of available and complete record information on a national level. Members of the NICS Travel Team attend and participate in various conferences, e.g., state clerks of courts conferences, national judges conferences, victims advocacy seminars, law enforcement employees seminars, state Attorneys General conferences, FFL awareness seminars, domestic violence conferences, and many others, to speak not only about the NICS but the comprehensive value of complete record information availability as well. The NICS Section personnel coordinate participation at such types of engagements with the hosting state and/or federal agency, and together optimum outreach and information sharing is achieved. Since 1999, various members of the NICS Section’s staff and the NICS Travel Team have journeyed to most of the states and U.S. territories, some on numerous occasions. As such, the NICS outreach initiative has continually gained momentum and swiftly increased in size and destination base. It was clear that the NICS Travel Team had implemented a movement that would reach far beyond the scope of the NICS Section; however, it was also evident that more was needed. One of the goals originally envisioned by the NICS Section became a reality in August 2003 with the implementation of the POC Support Team. The POC Support Team is comprised of a group of NICS employees dedicated to providing a centralized and consistent source for education and support to the POC states. The POC Support Team identifies, develops, and offers a wide range of information-sharing opportunities such as a general overview of the NICS; legal interpretations; appeal processing; permit processes; the NICS Index; firearm retrieval referrals; research strategies; misuse issues; state-to-state record retrieval resources; the interpretation of federal prohibitive criteria, and state and federal terminology; and specialized information pertaining to state-specific law to various interested agencies. Through effective liaison with POC state law enforcement/judicial agencies and/or other governmental agencies, the POC Support Team works passionately towards its goal of providing optimal service to the criminal justice processes in the United States and its territories. From September 2003 through December 2005, the POC Support Team has facilitated approximately 92 information-sharing sessions in over 50 separate locations in 20 states to over 2,800 participants whose duties vary from those of record clerks to administrative personnel and management, to law enforcement officers, corrections staff and management, Department of Public Safety and FBI officials, federal probation agencies, police department and sheriff’s office personnel and terminal agency controllers, etc., in addition to representatives of the offices of the state Attorney General. The POC Support Team continually receives requests to schedule additional supplementary information-sharing sessions from states that previously used their services, e.g., the decentralized states. Typically, in the decentralized states, there are many agencies that conduct NICS background checks. Ensuring that all such agencies within a state are processing NICS checks in a consistent manner does tend to pose challenges. As many of the smaller agencies may have a limited number of employees available for attendance at state-wide conferences, the POC Support Team avails their services to accommodate visitations to smaller state agencies as well, thus providing full in-state service to all who have identified the need. At times, this involves multiple trips to the same state; however, the end result, consistency and accuracy in processing, is realized as a direct result of the NICS Section’s information-sharing and outreach efforts. The services provided by the POC Support Team’s efforts have swiftly illustrated the NICS Section’s focus on customer service as a vital and integral part of the overall success of the entire NICS program and have served to create a more robust partnership between the FBI, the POC states, and the various integral components of the law enforcement and judicial community. Increasing the Number of Available and Complete Criminal History Dispositions Complete and readily available criminal history records serve both law enforcement and the general public in various ways. They provide comprehensive information needed to effect sound law enforcement decisions, effect public and officer safety planning initiatives, forewarn police officers about the type of individuals subject to routine traffic stops, and assist in determining sound and effective legal judgments. As such, it becomes even more crucial to identify and develop methods to efficiently and effectively seek and obtain missing disposition information in order for the NICS to operate as designed. When processing background checks that are delayed because of incomplete record information, the NICS Examiners must reach out to local, state, and other federal authorities in an attempt to obtain the record-completing data and render an accurate firearms or firearms/ explosives permit eligibility decision. As of December 31, 2005, the NICS Section’s staff has sought and obtained over 547,000 dispositions for posting to the CHRs. To maximize the use of all available resources, the NICS Section has developed various and integral support services to supplement the processes associated with establishing contact with external agencies to solicit for essential record-completing/clarifying information. The following information depicts many of support services implemented by the NICS Section that serve to enhance the outreach processes:

Table 4 Criminal History Record Updates Based on Documentation Obtained by the NICS Section as of December 31, 2005

On December 19, 2005, the NICS Section received a communication from the ICE providing notification that a planned power outage at the ICE’s Law Enforcement Service Center was scheduled later that month. As such, through effective and timely information sharing regarding the upcoming event, both agencies and the POC states were able to coordinate alternate measures for the efficient processing of Immigration Alien Queries (IAQs) and the subsequent completion of delayed background checks in as expeditious a manner as possible.