Siderits Technical Note

|

|

April 2010 - Volume 12 - Number 2 |

Technical Article

Richard Siderits

Chief

Experimental Pathology Division

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital at Hamilton

Hamilton, New Jersey

Jennifer Birkenstamm

Experimental Pathology Team Member

Medical Education Program

Experimental Pathology Division

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital at Hamilton

Hamilton, New Jersey

Francesca Khani

Experimental Pathology Team Member

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital at Hamilton

Hamilton, New Jersey

Evita Sadamin

Experimental Pathology Team Member

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital at Hamilton

Hamilton, New Jersey

Janusz Godyn

Administrative Director Southern Group

Department of Pathology

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital at Hamilton

Hamilton, New Jersey

Abstract | Introduction | Materials and Methods | Results |

Discussion/Conclusion | Acknowledgments | References

Criminal investigations have included the evaluation of chewing gum found at a crime scene. It is sometimes possible to retrieve valuable forensic information, including DNA, blood-group antigens, and tooth impressions. DNA analysis has been an invaluable tool in criminal investigations and has been used with “crime scene gum.” The analytical procedures used to retrieve DNA, however, may distort this malleable substance, thereby precluding accurate dental modeling. We describe a method for automated three-dimensional (3-D) laser scanning of crime scene gum using an inexpensive, automated 3-D laser scanner. A computer-assisted design (CAD) program is then used to define a virtual tooth surface that matches the imprint of the tooth impressions in the chewing gum. The resulting 3-D model can then be uploaded to a commercial rapid prototyping service to obtain precise 3-D plastic replicates of the digital file. If, following 3-D scanning, the original chewing gum is destroyed or distorted by forensic analysis, the digital file (or solid replicate model) can be used for future dental comparison.

Combining new and inexpensive technologies may provide more flexible approaches for dealing with familiar challenges in forensic science. One such challenge is the evaluation of chewing gum retrieved from a crime scene. This “crime scene gum” may provide information that can be used to corroborate DNA evidence with dental impressions (Bond and Hammond 2008; Nambiar et al. 2001). Chewing gum left at a crime scene has been used to determine ABO blood-group antigens of a suspect (Huckenbeck et al. 1988). When the gum is subjected to forensic analysis, the surface configuration of this highly malleable and easily distorted substance may be altered. Pressure and temperature changes within an evidence container, over time, may also distort its contours.

We present a procedure for nondestructive (noncontact) 3-D laser scanning of chewed gum into a digital file format that can be accomplished prior to DNA extraction. The resulting file can be used to accomplish virtual bite and tooth indentation comparisons using the computer-assisted design (CAD) program. It also may be used to re-create exact models of the chewing gum in solid plastic/resin form using either a computer-controlled numerical (CNC) milling machine or the recently available online solid-modeling capability. These solid models can be compared with dental records if the original evidence has been destroyed. Such comparisons between dental records and a 3-D model may reflect a reasonable approach to forensic investigation because similar techniques have been used in the design of dental implants from 3-D scans of artificial teeth (Sun et al. 2007).

We used an automated 3-D laser scanner (NextEngine, Santa Monica, California), which provides an affordable, reliable, and reproducible means for quickly scanning a three-dimensional object at an achievable resolution of 127 microns. We took a piece of chewed gum that had been air-dried for 24 hours, placed it on the tip of a tuberculin syringe needle, and positioned it on the fully robotic scanning stage of the laser scanner.

The scan parameters were set to automated 360-degree scan in eight segments with precision set to macro 0.005 inches. Next, the scan speed was set to fine 125 seconds, and the target surface was set to light in color with matte finish. The triangle size was set to 0.005, and smoothing was set to 1 with auto-align segments on. The scan time for a 360-degree modeling of the chewing gum with auto-align of the eight scanned segments totaled less than three minutes. The laser scanner mapped the surface images from a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera onto the three-dimensional surface defined by the laser scan paths. Finally, the model was subsequently checked for mesh overlap and holes before conversion to a COB object file format (.COB) for import into the trueSpace CAD program (Caligari, Redmond, Washington). The COB extension identifies the file as an object in the trueSpace CAD program.

Caligari’s trueSpace modeling program was used to import the object file, now titled “gum.cob.” The gum object was copied in this program several times to create at least three separate instances of the gum object within a trueSpace scene. Each of the two sides of the digital gum object was then subtracted from different sides of the virtual block in the program, thereby creating a 3-D contour of the teeth that made the impression in the gum. Two other instances of the gum objects were then sunk to half their depth and “fused” into the sides of the block to represent the two surfaces of the gum.

The virtual block then represented a single object within the trueSpace scene. It showed the shape of the impressions in the gum as well as the contour of the teeth that formed these impressions. The “scene” file, which included the gum object and the virtual bite/tooth contour block, was saved. From this single block, the tooth surface contours or the digital gum itself may be re-created as a solid object anytime. For this study, the gum object was saved separately as an STL (stereolithography) file to upload to the Shapeways (Eindhoven, Netherlands) Web site for rapid prototyping.

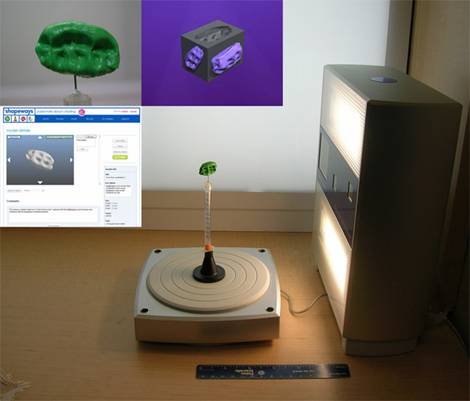

Shapeways is a Web-based rapid prototyping service that offers object model production from digital files using several different accretion prototyping platforms, which include the Stratasys FDM (fused deposition modeling) Fortus 400 mc (Fortus 3D Production Systems, Stratasys, Eden Prairie, Minnesota) (with dimensional accuracy of 100 microns); the Connex500 (Objet Geometries, Rehovot, Israel); and the EOS SLS (selective laser-sintering) Formiga P 100 (EOS, Krailling, Germany) platforms. The digital file is uploaded to the Shapeways Web site and is automatically screened for “manifold error” and “water tightness” and is then displayed as either a private password-protected file or “public viewable” model. Once uploaded to the Web site, the file is then available for rapid prototyping using photopolymer deposition. We uploaded the 3-D model of the gum and subsequently ordered clear resin and white plastic models using the order entry page on the Web site. Images representing the steps in this process are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Background image: NextEngine automated 3-D laser scanner with gum mounted on needle tip. Insert, upper left: closeup of gum on needle mount. Insert, upper middle: Caligari trueSpace “tooth block” representing the shape of tooth surfaces from both sides of the gum on the sides of the virtual cube. The top surface shows a void or subtracted gum space, which corresponds to the shape of the tooth surface that made the indentation in the surface of the gum. Insert, lower left: Shapeways Web site, solid model order entry page.

The entire process of (1) scanning the chewing gum with the NextEngine laser scanner, (2) re-creating virtual tooth contours from the impressions in the gum, and (3) uploading the 3-D digital file of the gum to the rapid prototyping site (with online ordering of deliverable solid models) took less than 10 minutes. The solid plastic models of the digital file arrived by mail within a few days (Figure 2). Figure 3 displays side-by-side images of the actual chewing gum (left) and the plastic model (right).

Figure 2 Top and Bottom: Models of human hamate (wrist) bones and chewing gum, scanned with the NextEngine laser scanner, reviewed with the trueSpace CAD program, and produced as solid plastic by the Shapeways online rapid prototyping service. The bottom photo presents a different view and background of one of the bone models and one of the gum models in the top photo.

Figure 3: Side-by-side images of the actual chewing gum (left) and the plastic model (right)

Crime scene gum may be used in criminal investigations and may provide valuable biological information obtained from its indented surfaces. The gum, however, is a malleable substance, and the process of isolating blood-group antigens or DNA may destroy or distort the shape of the gum. Distortion of the surface contours thereafter may prevent reliable evaluation of tooth imprints.

Over time, the gum may be distorted or disrupted in an evidence container. Therefore, it may be useful to obtain an accurate three-dimensional digital model of the gum prior to additional study or storage. A 3-D digital model of the gum may be used to create a virtual tooth contour. Once the data are saved as a digital 3-D file, a new solid model of the gum (or associated tooth contour) can be fabricated anytime and used to compare tooth impressions or bite marks. The method we describe permits noncontact, nondestructive, automated 3-D laser scanning and digital modeling of crime scene gum. The same techniques may be used in other circumstances on living or nonliving (desiccated) biological materials.

Many 3-D laser scanners cost upwards of $20,000 and are too large to be utilized in the field. We sought a cost-effective (less than $3000 with adequate resolution) and practical approach to 3-D laser scanning at a crime scene and felt that the NextEngine product was superior in this regard.

The NextEngine 3D laser scanner has a compact design and demonstrates adequate resolution of 0.005 inch (127 microns), and the compatible trueSpace software has an intuitive interface that we mastered in a few minutes. The texture maps (images obtained from the CCD camera) and 3-D surfaces are meshed and merged automatically by the software. The algorithms for these functions are robust and user-friendly. Any discontinuities may be aligned manually by dragging reference markers onto the scans or by using the “Fill” algorithms in the software. Other commercially available 3-D laser scanners (for less than $3000)—such as the FlexScan3D scanner (3D3 Solutions, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) and the REVscan 3D scanner (Creaform, Lévis, Quebec, Canada)—can be used. Other CAD software programs—such as Blender (The Blender Foundation, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Blender is available free at http://www.blender.org) and Rhino 3D (McNeel North America, Seattle, Washington. See http://www.rhino3d.com)—also may be used.

The CAD program allows rapid visualization with model fusion and volume subtraction, allowing bite-mark “back-modeling.” It can also model other scanned objects, including bones, toolmarks, or tooling and, when combined with the laser scanner, can provide physics simulation for splatter/castoff, ballistics, and bite-mark reverse imprinting. Material deformation and manipulation of environmental factors also are available.

Each of these three components will run on a standard notebook computer (4 GB RAM), which enables field use for on-site crime scene scans. The scanner has a standard tripod mount at its base. Structures larger than gum—for example, surfaces requiring immediate scanning or that would not fit on the robotic stage (bite marks, tire tread, dents, toolmarks, footprints in soft material, blood spatter/castoff, or even digital 3-D virtual “death masks”)—can be scanned in wide-angle mode. In forensic odontology, bite-mark analysis is an ideal example of the need for immediate 3-D scanning (Spitz 1993). Given the documented precision and accuracy of the NextEngine 3D laser scanner and the Shapeways automated milling platforms, we believe that bite-mark analysis using the resulting model with tooth impressions is feasible.

In summary, we illustrate a method for quickly and inexpensively (1) scanning crime scene gum by using a desktop, compact, automated 3-D laser scanner (NextEngine); (2) creating a virtual tooth imprint model using the trueSpace CAD program; and (3) using an online rapid prototyping service for obtaining solid models of the scanned objects. The online rapid fabrication services are flexible, robust, and easily accomplished by uploading the digital file. The combination of these techniques may also support a wide range of uses in criminal investigations.

We thank the reviewers for their efforts.

Bond, J. W. and Hammond, C. The value of DNA material recovered from crime scenes, Journal of Forensic Sciences (2008) 53:797–801.

Huckenbeck, W., Bonte, W., Eckrodt, H., and Stancu V. [ABO determination of chewing gum residues]. Archiv Für Kriminologie (1988) 181(5–6):162–6.

Nambiar, P., Carson, G., Taylor, J. A., and Brown, K. A. Identification from a bitemark in a wad of chewing gum, The Journal of Forensic Odonto-Stomatology (2001) 19:5–8.

Spitz, W. U. Forensic odontology. In: Spitz and Fisher’s Medicolegal Investigation of Death: Guidelines for the Application of Pathology to Crime Investigation. 3rd ed. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois, 1993, pp. 127–132.

Sun, Y.-C., Lü, P.-J., Wang, Y., Han, J.-Y., and Zhao, J.-J. [Research and development of computer aided design and rapid prototyping technology for complete denture]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi [Chinese Journal of Stomatology] (2007) 42:324–9.

01.03.11

| FSC Links |

|

- Table of Contents |