Crime in Schools and Colleges

Crime in Schools and Colleges:

A Study of Offenders and Arrestees Reported via National Incident-Based Reporting System Data

Introduction

Schools and colleges are valued institutions that help build upon the nation’s foundations and serve as an arena where the growth and stability of future generations begin. Crime in schools and colleges is therefore one of the most troublesome social problems in the Nation today. Not only does it affect those involved in the criminal incident, but it also hinders societal growth and stability. In that light, it is vital to understand the characteristics surrounding crime in schools, colleges, and universities and the offenders who reportedly commit these offenses so that law enforcement, policy makers, school administrators, and the public can properly combat and reduce the amount of crime occurring at these institutions.

Tremendous resources have been used to develop a myriad of federal and nonfederal studies that focus on identifying the characteristics surrounding violent crime, property crime, and/or crimes against society in schools. The objective of such studies is to identify and measure the crime problem facing the Nation’s more than 90,000 schools and the nearly 50 million students in attendance.1 The findings of these studies have generated significant debates surrounding the actual levels of violent and nonviolent crimes and the need for preventative policies. Some research indicates there has been an increase in school violence activities, such as a study from the School Violence Resource Center which showed that the percentage of high school students who were threatened or injured with a weapon increased from 1993 to 2001.2 Other research notes decreases in student victimization rates for both violent and nonviolent crimes during a similar time period (1992–2002).3 Moreover, the circumstances surrounding crime in schools, colleges, and universities are not always the ones that gain wide notoriety. The most significant problems in schools are not necessarily issues popularly considered important as most conflicts are related to everyday school interactions.4 Furthermore, the National Center for Education Statistics notes that “it is difficult to gauge the scope of crime and violence in schools without collecting data, given the large amount of attention devoted to isolated incidents of extreme school violence.”5 These conflicting conclusions concerning the ability to measure the overall situation of crime in school, college, and university environments make it difficult for policy makers to assess the effectiveness of policies and their impact on this phenomenon.

The Nation’s need to understand crime as it occurs at schools, colleges, and universities was officially placed into law by the US Congress with the passage of the Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act6 (Clery Act). Prompted by the 1986 rape and murder of a 19-year-old Lehigh College student in her dorm room, the Clery Act requires universities and colleges to report crime statistics, based on Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) definitions, to the Department of Education (ED) and to disclose crime statistics to nearly 16 million students attending any one of the Nation’s approximately 4,200 degree-granting post-secondary institutions.7 The Clery Act, most recently amended in 2000, demands stiff financial penalties from post-secondary institutions found to misreport crime statistics to the ED. Such penalties are currently set at $27,500 per incident.8 Though the Clery Act requires colleges and universities to report their crime data to the ED, neither it nor any other Federal legislation requires these institutions to report the data to the UCR Program.

Situations surrounding crime at school locations vary based on the offender’s motive and the intended victim. For example, incidents involving student offenders and student victims constitute the stereotypical definition of crime at schools, colleges, and universities where the offender and victim are present to participate in the activities occurring at the institution. However, there are situations involving adult and/or juvenile offenders and victims, where the school serves only as an offense location because neither the offender nor the victim is present to participate in school functions. Criminal acts due to political motivation, hate crimes, and crimes perpetrated by offenders against victims who are not instructors or students and have no other relation to the school are examples of such situations.

In an attempt to shed light on crime in schools, colleges, and universities, this study used incident-based crime data the FBI received from a limited set of law enforcement agencies through the UCR Program. Some of the findings are perhaps contrary to popular perceptions; for example, over the 5-year study period, the use of knives/cutting instruments was over three times more prevalent than the use of a gun. (Based on Table 8.) Other findings reflect conventional wisdom; for example, males were nearly 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for crime in schools and colleges than females. (Based on Table 12.)

Objective

Data from a variety of sources about crime in schools and colleges and characteristics of the people who commit these offenses provide key input in developing theories and operational applications that can help combat crime in our Nation’s schools, colleges, and universities. Given the myriad of data available, the objective of this study is to particularly analyze data submitted to the FBI’s UCR Program by law enforcement agencies. It examines specific characteristics of offenders and arrestees who participated in criminal incidents at schools and colleges from 2000 through 2004. Because the study dataset is not nationally representative, readers should be cautious in attempting to generalize the findings. (See the Methodology section for data caveats.)

Data

The data used for this study reside in databases maintained by the UCR Program, which the FBI manages according to a June 11, 1930, congressional mandate. Law enforcement agencies nationwide may choose to participate in the UCR Program by voluntarily submitting crime data in one of two formats: the Summary Reporting System or the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). Not all UCR data, however, reflect sufficient detail to be useful for this study. Therefore, only the UCR data gathered via the NIBRS were used.

Methodology

The NIBRS was designed in the 1980s to enhance the Summary Reporting System by capturing detailed information at the incident level. Once the system was developed, the FBI began collecting NIBRS data in 1991 from a small group of law enforcement agencies. By the end of 2004, approximately 33 percent of the Nation’s state and local law enforcement agencies covering 22 percent of the US population reported UCR data to the FBI in the NIBRS format. (See Table 1.) In addition, the percentage of crime reported to the UCR Program via the NIBRS had risen from 13 percent in 2000 to 20 percent in 2004. However, growing increases in the amount of crime reported via NIBRS do not necessarily indicate increases in crime in general or the actual occurrences of crime in schools. However, increases in the number of NIBRS offenses may be largely the result of more law enforcement agencies using the NIBRS data collection format.

Table 1: UCR Participation via the NIBRS, by Year |

|||||

| Year of Incident | |||||

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | |

| United States Population | 281,421,906 | 285,317,559 | 287,973,924 | 290,788,976 | 293,655,404 |

| Percent of US Population Covered by Agencies Reporting via the NIBRS | 16% | 17% | 17% | 20% | 22% |

| Number of Agencies Participating in the UCR Program via the NIBRS1 | 3,801 | 4,259 | 4,302 | 5,271 | 5,735 |

| Percent of Agencies Reporting via the NIBRS | 22% | 25% | 25% | 31% | 33% |

| Percent of Crime Reported to the UCR Program via the NIBRS | 13% | 15% | 18% | 17% | 20% |

1 Based on law enforcement agencies that submitted their UCR data to the FBI in accordance with NIBRS reporting requirements for inclusion in the annual NIBRS database.

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

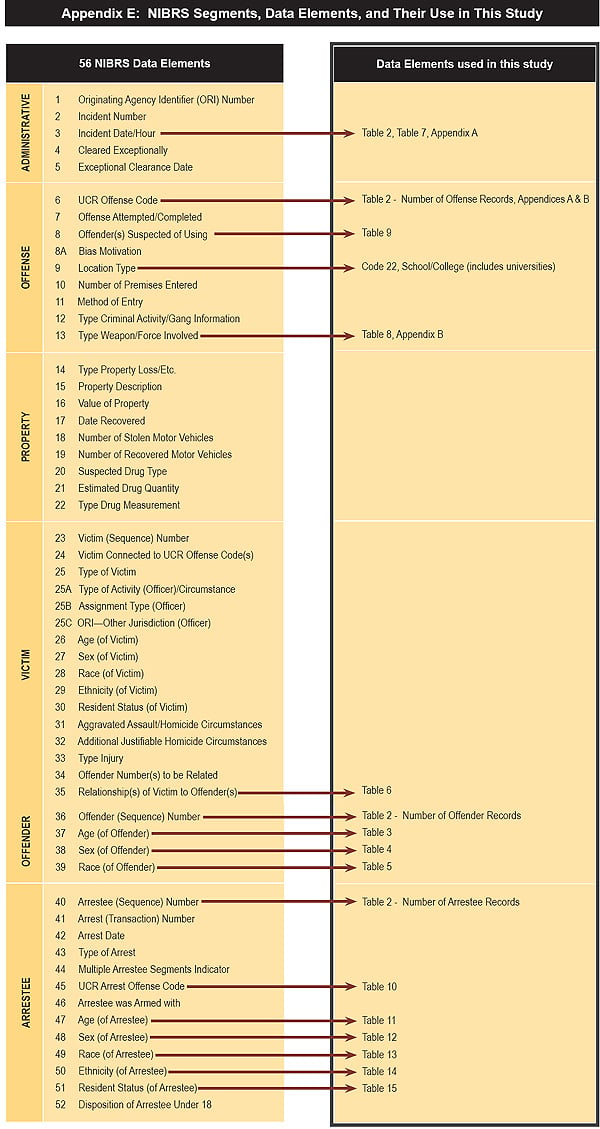

Using a combination of six possible data segments (administrative, offense, victim, property, offender, and arrestee), the NIBRS captures information on criminal incidents involving any of 22 offense categories made up of 46 specific crimes. To date, the NIBRS offers 56 data elements, i.e., data fields, that law enforcement may use to capture descriptive data about the victims, offenders, and circumstances of criminal incidents and arrests. Examples of NIBRS data elements include UCR Offense Code,Type of Victim, and Age of Offender (see Appendix E for a complete list of data elements). 9 Furthermore, each of the 56 data elements is translated into a series of codes that specify the information being collected.

Of particular importance to the present study is the NIBRS data element Location Type, specifically Code 22,10 which identifies offenses occurring at schools and colleges. All the crime data used in the tables and discussions throughout this study were reported by law enforcement as occurring at NIBRS Location Type, Code 22, which hereafter is referred to as school(s), unless otherwise noted.

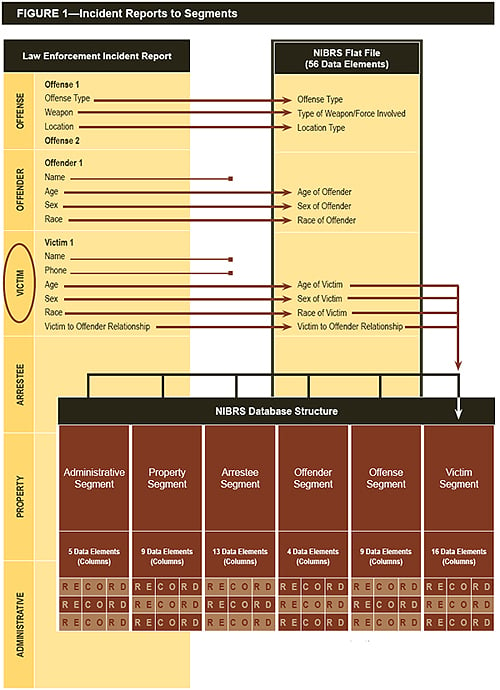

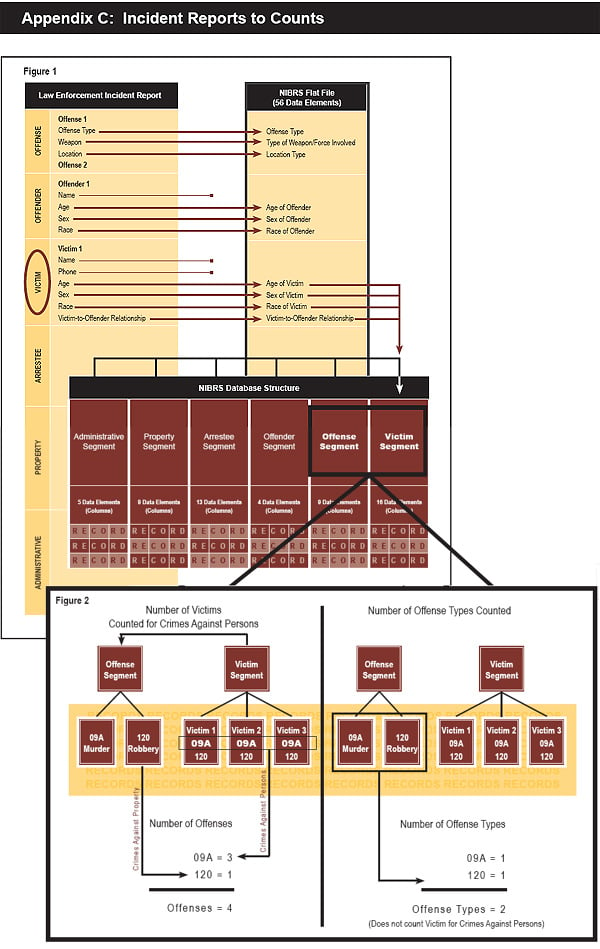

As illustrated in Figure 1, an incident report contains various types of data collection segments in addition to the administrative segment. The report may also include multiple segment records within one or more segments if the incident should warrant them. For example, an incident occurred during which three victims were held up on school property by two offenders using guns. The offenders shot and killed the victims and were subsequently arrested. This incident will have one administrative record, two offense records, various property records for the stolen or recovered property, three victim records, two offender records, and two arrestee records separated into the appropriate segments in the NIBRS database structure.

This study focuses primarily on the offender and arrestee data records; it looks at other records only as they pertain to offenders. Using the narrowly-defined set of data records, the study specifically addresses incident characteristics (Tables 2 and 7), offender characteristics (Tables 3-5), victim-to-offender relationships (Table 6), offense characteristics (Tables 8 and 9), and arrestee characteristics (Tables 10-15). Expanding Tables 2 and 8, Appendices A and B show the number of offenses by offense type by year and the weapon type by offense type, respectively.

This graphic sample illustrates the extraction of the Victim data elements from the Incident Report to the NIBRS Flat File and how they are segmented in the NIBRS Database Structure.

Throughout this study, age groups are aggregated and cross tabulated to help readers view the traits of offenders and arrestees. These age groups are formulated based upon the following age divisions: Birth to 4 years old, 5 to 9 years old, 10 to 12 years old, 13 to 15 years old, 16 to 18 years old, and 19 years or older.

Additional considerations for this study follow:

- The term gun refers collectively to all firearm codes found in the NIBRS format, including: firearm, handgun, rifle, shotgun, and other firearm types.11 Furthermore, information for type weapon/force involved is only collected for Murder and Nonnegligent Manslaughter, Negligent Manslaughter, Justifiable Homicide,Kidnapping/Abduction, Forcible Rape, Forcible Sodomy, Sexual Assault with an Object, Forcible Fondling, Robbery, Aggravated Assault, Simple Assault,Extortion/Blackmail, and Weapon Law Violations.

- Victim-to-offender relationships are only collected for Murder and Nonnegligent Manslaughter, Negligent Manslaughter, Justifiable Homicide,Kidnapping/Abduction, Forcible Rape, Forcible Sodomy, Sexual Assault with an Object, Forcible Fondling, Robbery, Aggravated Assault, Simple Assault,Intimidation, Incest, and Statutory Rape.

- Offenders may be suspected of using alcohol, computers, and/or drugs in an offense. Because more than one of these codes can be collected on any given offense record, there may be multiple counts of use in incidents. Multiple counts can be generated in two ways. An incident with one offense record may be associated with the use of alcohol and drugs. Another incident may contain two offense records, one offense indicating the suspected use of alcohol and a second offense where the offender is suspected of using drugs. Both types of incidents will indicate that the offender was suspected of using both alcohol and drugs. Caution is needed when interpreting this information.

- Frequency tables and cross tabulations are used to examine the characteristics discussed for the 5-year study time frame. See the Limitations section on cautions for comparing frequencies from year to year.

- The data used in this study reflect the NIBRS submissions originally made for each year within the 5-year period. They do not include data that were subsequently reported via time-window submissions.12

Special Offense Definitions

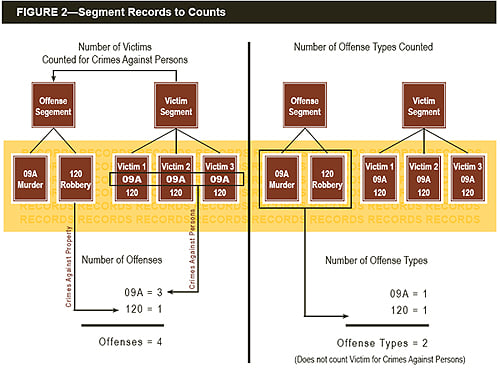

An important distinction must be made in the context of this study concerning the use of the term offense. In the UCR Program, the term offense has a very particular definition that employs a series of rules defining the way offenses are counted. Specifically, the number of offenses for crimes against persons is determined by the number of victims, while the number of offenses for crimes against property and society is based on each distinct operation.

This study also introduces a nontraditional counting method that counts the number of records associated with the offense segment. Within any incident reported in NIBRS, there is only one record reported for each unique offense code. In NIBRS, there are 46 Group A offense codes in which full incident information is collected and 11 Group B offense codes where only arrestee information is reported. This study uses the number of offense records in Table 2 and Appendix B which shows weapon type by offense type. The effect of this counting method is that the number of victims is not considered when counting the number of offense records. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2, on the following page, illustrates how offenses and offense records are counted in NIBRS for a hypothetical incident with three victims of homicide who were also robbed. The left of the figure shows the counts of offenses which include three counts of homicide, Code 09A, and one of robbery, Code 120, for a total of four offenses. Because homicide is a crime against persons, one offense is tallied for each victim, while robbery, a crime against property, only counts one offense for each distinct operation, regardless of the number of victims. However, on the right of the figure where offense records are counted, only one count of homicide and one of robbery are used to determine the sum of offense records. Therefore, the number of offense records equals two, one for each unique offense type in this example.

Because this study focuses on offenders and arrestees, this approach is beneficial, particularly when examining weapon type by offense type (see Appendix B), since it eliminates the natural weighting that occurs when using traditional UCR offense counting rules based on the number of victims. For example, because the weapon type is associated with the offense segment in NIBRS, an incident involving three murder victims has three offenses connected to the weapon type, overestimating the presence of that weapon type. However, if the offense type is maintained as the unit of analysis for weapon type, the weighting of weapon types by the number of victims is avoided. Of greater relevance to the objective of this study are the types of offenses that offenders commit in schools. Certainly, studies involving NIBRS data that focus on the victim or offense segments require the examination of offenses based on the traditional UCR offense counting practices.

Incident Characteristics

Of the 17,065,074 incidents reported through the NIBRS by law enforcement from 2000 to 2004, 558,219 (3.3 percent) occurred at schools. There were 589,534 offense records, 619,453 offenses, and 688,612 offender records reported in those incidents. The statistics discussed in this report are based on the 476,803 offenders for whom at least one attribute (age, gender, race, and/or number of offenders) was known.13 However, none of the characteristics for offenders (age, gender, race, or number of offenders) were known in 211,809 of the 688,612 offender records. During these 5 years, there were 181,468 arrestees associated with crime in schools. (See Table 2.) According to UCR guidelines, the arrestee may be different than the person who was reported as the offender.

Table 2: Overview of Crime in Schools, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | 5-Year Total | |||||

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | ||

| Number of Incidents: |

17,065,074 | |||||

|

In all locations

|

2,616,448 | 3,269,022 | 3,458,569 | 3,684,154 | 4,036,881 | |

|

In schools

|

84,627 | 109,239 | 110,467 | 121,765 | 132,121 | 558,219 |

|

Percent of Incidents in Schools

|

3.2 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| Characteristics of Incidents in Schools | ||||||

|

Number of Offenses

|

92,242 | 120,938 | 123,200 | 135,489 | 147,584 | 619,453 |

|

Offense Records

|

88,687 | 115,642 | 117,341 | 128,542 | 139,322 | 589,534 |

|

Offender Records1

|

102,655 | 134,088 | 136,358 | 150,913 | 164,598 | 688,612 |

|

Unknown Offender Records2

|

33,239 | 42,784 | 41,761 | 46,106 | 47,919 | 211,809 |

|

Persons Arrested

|

24,662 | 33,280 | 34,360 | 41,057 | 48,109 | 181,468 |

1Includes the number of unknown offender records.

2Unknown offender records are reported when nothing is known about the offenders in the incident, including age, gender, race, and number of offender(s).

See p. 99 of NIBRS Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines, August 2000, for more

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

Offender Characteristics

Age was known for 393,938 offenders.14 Of those, most (38.0 percent) were 13-15 year olds. The second largest group was 16-18 year olds (30.7 percent), followed by those offenders aged 19 or older (18.2 percent) and 10-12 year olds (11.0 percent). Offenders 9 years old or under accounted for 2.1 percent of the offenders where the age was known. By looking at only those offenders for whom the age was known, offenders 18 years of age or younger were 4.5 times more likely to be involved in crime at schools than older offenders. There were 82,865 offenders for whom the age was unknown (but other characteristics, such as gender and/or race, were known to the police). (Based on Table 3.)

Table 3: Offenders1 of Crime in Schools, by Age2, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Age (Years) | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| 0–4 | 35 | 49 | 74 | 53 | 76 | 287 |

| 5–9 | 1,246 | 1,807 | 1,521 | 1,563 | 1,775 | 7,912 |

| 10–12 | 5,845 | 8,541 | 8,859 | 9,557 | 10,640 | 43,442 |

| 13–15 | 20,244 | 28,171 | 29,697 | 33,163 | 38,347 | 149,622 |

| 16–18 | 16,732 | 22,506 | 23,564 | 27,533 | 30,624 | 120,959 |

| 19 or Older | 10,748 | 13,608 | 14,295 | 15,637 | 17,428 | 71,716 |

| Unknown Age1 | 14,566 | 16,622 | 16,587 | 17,301 | 17,789 | 82,865 |

| Total Offenders3 | 69,416 | 91,304 | 94,597 | 104,807 | 116,679 | 476,803 |

1At least one other characteristic (gender, race, or number of offenders) was reported.

2Law enforcement may report a range of ages. NIBRS reports the midpoint of the age range (e.g., offender age 25-35 is reported as 30).

3Over the 5-year study period, there were 211,809 offenders for whom the age, gender, race, and number of offenders were not reported.

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

For the 5-year study period, the majority (313,556 or 76.7 percent) of the offenders about whom gender was known were males, who were reported as offenders 3.3 times more often than females. Of the offenders for whom age, race, and/or number of offenders was known, the gender was unknown to law enforcement for 67,796 offenders (14.2 percent). (Based on Table 4.)

Table 4: Offenders1 of Crime in Schools, by Gender, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Gender | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| Male | 45,011 | 60,358 | 61,831 | 69,288 | 77,068 | 31,556 |

| Female | 12,560 | 17,471 | 18,876 | 21,248 | 25,296 | 95,451 |

| Unknown Gender1 | 11,845 | 13,475 | 13,890 | 14,271 | 14,315 | 67,796 |

| Total Offenders2 | 69,416 | 91,304 | 94,597 | 104,807 | 116,679 | 476,803 |

1At least one other characteristic (age, race, or number of offenders) was reported.

2Over the 5-year study period, there were 211,809 offenders for whom the age, sex, race, and number of offenders were not reported.

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

Of the 394,173 offenders about whom race was known, white offenders accounted for 71.1 percent (280,178); black offenders, 27.4 percent (107,878); and all other races combined, less than 2 percent (6,117).15 When race was known, whites were 2.5 times more likely to be reported as an offender at a school than were all other races combined. Of the total offenders about whom age and/or gender were known (476,803), race was unknown for 17.3 percent. (Based on Table 5.)

Table 5: Offenders1 of Crime in Schools, by Race, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Race | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| White | 41,220 | 53,862 | 55,735 | 61,849 | 67,512 | 280,178 |

| Black | 13,319 | 19,876 | 20,918 | 24,225 | 29,540 | 107,878 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 584 | 783 | 767 | 936 | 915 | 3,985 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 282 | 359 | 432 | 433 | 626 | 2,132 |

| Unknown Race1 | 14,011 | 16,424 | 16,745 | 17,364 | 18,086 | 82,630 |

| Total Offenders2 | 69,416 | 91,304 | 94,597 | 104,807 | 116,679 | 476,803 |

1At least one other characteristic (gender, age, or number of offenders) was reported.

2Over the 5-year study period, there were 211,809 offenders for whom the age, sex, race, and number of offenders were not reported.

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

Victim-to-Offender Relationships

Table 6 provides breakdowns for victim-to-offender relationships, an important aspect to understand when examining crime at schools. It is also important to understand the information in Table 6 reflects a count of relationships and not merely the number of victims and/or offenders. For example, if an incident has four victims and two offenders, there are eight relationship pairings noted in the table (4 victims multiplied by 2 offenders equals 8 relationships).

By far, the relationship type most often reported for crime in schools was Acquaintance, with 107,533 instances occurring during the 5-year study period. When Acquaintance was combined with the Otherwise Known category (50,486 instances), these two categories were 3.3 times more likely to occur as the relationship than were all other victim-to-offender relationships in which the relationship was known. The relationship Victim was Offender was reported for 15,539 occurrences, or 7.5 percent of known relationships. This type of relationship is one in which all participants in the incidents were victims and offenders of the same offense, such as assaults being reported as a result of a brawl or fight.16 Stranger was reported for 7.5 percent (15,511 instances) of the relationships. The remaining percentages were widely dispersed among all other relationship categories.

Table 6: Relationship1 of Victims to Offenders of Crime in Schools, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Relationship (victim was . . .) | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| Acquaintance | 14,074 | 20,429 | 22,102 | 23,647 | 27,281 | 107,533 |

| Otherwise Known | 6,326 | 8,960 | 9,845 | 11,192 | 14,163 | 50,486 |

| Victim was Offender2 | 1,429 | 2,805 | 3,173 | 3,543 | 4,589 | 15,539 |

| Stranger | 2,301 | 3,060 | 3,045 | 3,405 | 3,700 | 15,511 |

| Friend | 1,300 | 1,465 | 1,719 | 1,501 | 2,006 | 7,991 |

| Boyfriend/Girlfriend | 452 | 609 | 600 | 741 | 888 | 3,290 |

| Child | 187 | 220 | 266 | 245 | 326 | 1,244 |

| Spouse | 117 | 162 | 155 | 170 | 163 | 767 |

| Other Family Member | 117 | 111 | 112 | 131 | 159 | 630 |

| Neighbor | 110 | 91 | 94 | 116 | 130 | 541 |

| Sibling | 84 | 76 | 102 | 124 | 144 | 530 |

| Parent | 66 | 96 | 95 | 79 | 141 | 477 |

| Employee | 44 | 76 | 69 | 103 | 146 | 438 |

| Ex-Spouse | 54 | 67 | 84 | 95 | 78 | 378 |

| Employer | 28 | 32 | 43 | 33 | 43 | 179 |

| Babysittee (the baby) | 26 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 26 | 123 |

| In-Law | 10 | 26 | 25 | 27 | 32 | 120 |

| Stepchild | 12 | 28 | 15 | 22 | 23 | 100 |

| Child of Boyfriend/Girlfriend | 14 | 6 | 14 | 14 | 19 | 67 |

| Stepparent | 12 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 13 | 65 |

| Homosexual Relationship | 2 | 7 | 9 | 16 | 30 | 64 |

| Common-Law Spouse | 7 | 18 | 11 | 10 | 16 | 62 |

| Grandchild | 9 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 15 | 48 |

| Stepsibling | 6 | 4 | 10 | 15 | 6 | 41 |

| Grandparent | 0 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 26 |

| Relationship Unknown | 4,752 | 7,089 | 7,184 | 7,815 | 8,721 | 35,561 |

| Total Relationships1 | 31,539 | 45,487 | 48,822 | 53,096 | 62,867 | 241,811 |

1There is not a 1:1 correspondence of relationships to incidents. For example, if an incident has 4 victims and 2 offenders, 8 relationship pairings are noted (4 victims multiplied by 2 offenders equals 8 relationships).

2Victim was Offender is a relationship in which all participants in the incidents were victims and offenders of the same offense, such as assaults being reported as a result of a brawl or fight.

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

Offense Characteristics

A rich level of detail about offense characteristics is captured in the NIBRS format. Of particular interest for the present study is the month of occurrence/report, use of weapons/force, and suspected use of alcohol, computers, and/or drugs by offenders.17

Table 7 provides the number of incidents as they were reported by month for each year of the study. The month with the most incidents for the 5-year period was October, with a total of 66,726. Among the 5-year totals, the month of March had the second-highest number of reported incidents (58,363), and September followed with 57,417 incidents. It should be noted, however, that on some occasions, the date of the incident is unknown to law enforcement.18 For example, a school principal notices vandalism at the school on Monday morning and reports the crime. Though the principal knows the vandalism did not occur before Friday afternoon, neither he nor law enforcement can determine whether it happened Friday evening, Saturday, Sunday, or early Monday morning. Therefore, law enforcement reports the earliest date in which the incident could have occurred (Friday) as the date of the incident. In other instances, a crime occurs during a holiday or summer break and is not discovered and reported until the start of school or after the change of a month. Law enforcement enters the date of the report as the date of the incident, potentially counting the incident in a different month than when it occurred. In this study, incidents in which the dates of reports were used accounted for 19.5 percent of the incidents reported as having occurred in school locations. However, the percentages by month for the dates of reports and the actual dates of incidents are very similar (within 0.5 percent for each month), which indicates that only a small percentage of incidents may have occurred in prior months.

Table 7: Incident and Report Date of Crime in Schools by Month, by Year |

|||||||

| Year of Incident | |||||||

| Month | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | Incident Dates 5-Year Total |

Report Dates 5-Year Total |

| January | 6,660 | 9,275 | 9,717 | 10,010 | 10,610 | 46,272 | 9,160 |

| February | 8,316 | 9,781 | 10,394 | 10,168 | 12,808 | 51,467 | 9,794 |

| March | 9,069 | 12,056 | 10,362 | 12,393 | 14,483 | 58,363 | 11,739 |

| April | 7,739 | 10,520 | 11,058 | 12,462 | 13,038 | 54,817 | 10,287 |

| May | 8,230 | 10,920 | 11,050 | 12,297 | 12,337 | 54,834 | 10,883 |

| June | 4,527 | 5,187 | 4,901 | 5,992 | 6,019 | 26,626 | 5,705 |

| July | 3,102 | 3,880 | 3,894 | 4,213 | 4,245 | 19,334 | 4,132 |

| August | 4,093 | 5,167 | 5,267 | 5,556 | 6,063 | 26,146 | 4,615 |

| September | 8,814 | 10,539 | 11,490 | 12,852 | 13,722 | 57,417 | 10,888 |

| October | 10,136 | 12,919 | 13,183 | 15,192 | 15,296 | 66,726 | 12,893 |

| November | 8,090 | 10,553 | 10,829 | 11,264 | 13,178 | 53,914 | 10,538 |

| December | 5,851 | 8,442 | 8,322 | 9,366 | 10,322 | 42,303 | 7,994 |

| Total Incidents | 84,627 | 109,239 | 110,467 | 121,765 | 132,121 | 558,219 | 108,628 |

Note: Report date counts are included in incident date totals. See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

The particular types of weapons/force used are shown in Table 8.19 The most common weapon type reported was personal weapons (the offender’s hands, fists, feet, etc.), which were reported 98,394 times. Personal weapons were 3.4 times more likely to have been reported than any other weapon type (excluding None and Unknown). The weapon type None was reported 16,260 times in the study, which is relatively large compared to the other known weapon types. See the table in Appendix B for a cross-table of weapon type by offense type.

Of the 3,461 times guns were reportedly used, handguns were most often reported (58.0 percent).20 Knives/cutting instruments were reportedly used 10,970 times, which outweighs the number of times guns were used by 3.2 to 1. Law enforcement reported the weapon type Other 11,680 times.21 This is quite significant when compared to specific weapon types; however, NIBRS data cannot indicate what types of weapons would fit into this category. The Other weapon category may contain, for example, acid, pepper spray, belts, deadly diseases, scalding hot water, or other weapon types not covered by the NIBRS weapon type codes.

Table 8: Type of Weapon/Force Used in Crime in Schools, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Weapon Type/Force Used | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| Personal Weapons | 12,945 | 17,830 | 20,636 | 21,933 | 25,050 | 98,394 |

| None | 2,702 | 3,114 | 2,974 | 3,294 | 4,176 | 16,260 |

| Other | 1,775 | 2,311 | 2,332 | 2,420 | 2,842 | 11,680 |

| Knife/Cutting Instrument | 1,511 | 2,082 | 2,080 | 2,445 | 2,852 | 10,970 |

| Handgun | 307 | 376 | 398 | 430 | 497 | 2,008 |

| Blunt Object | 283 | 404 | 394 | 455 | 469 | 2,005 |

| Firearm (type not stated) | 94 | 131 | 103 | 135 | 146 | 609 |

| Other Firearm | 74 | 107 | 92 | 155 | 154 | 582 |

| Explosives | 145 | 139 | 93 | 89 | 95 | 561 |

| Motor Vehicle | 43 | 52 | 46 | 59 | 71 | 271 |

| Fire/Incendiary Device | 36 | 34 | 42 | 36 | 88 | 236 |

| Rifle | 23 | 33 | 33 | 24 | 37 | 150 |

| Shotgun | 15 | 24 | 30 | 19 | 24 | 112 |

| Drugs/Narcotics/Sleeping Pills | 9 | 4 | 8 | 14 | 6 | 41 |

| Poison | 1 | 8 | 4 | 11 | 16 | 40 |

| Asphyxiation | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 14 |

| Unknown | 593 | 1,128 | 1,163 | 1,069 | 1,098 | 5,051 |

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

Table 9 provides the reported instances in each offense record in which the offenders were suspected of using alcohol, computers, and/or drugs.22 The data show that such use was minimal in situations occurring at schools during the 5-year study period. Of the 589,534 offense records, reports of offenders suspected of using drugs totaled 32,366, while reports of alcohol use totaled 5,844. Suspected computer use by offenders was reported for 1,655 instances. The offender’s suspected use of one or more of these items may have occurred during or shortly before the incident, and the use may have occurred in another location.

Table 9: Reports of Offenders Suspected of Using Alcohol, Computers and/or

|

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Use Category | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| Alcohol | 998 | 1,134 | 1,154 | 1,212 | 1,346 | 5,844 |

| Computer Equipment |

376 | 409 | 306 | 256 | 308 | 1,655 |

| Drugs/ Narcotics |

4,478 | 6,233 | 6,146 | 7,253 | 8,256 | 32,366 |

| Not Applicable | 83,194 | 108,315 | 110,051 | 120,163 | 129,745 | 551,468 |

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

Arrestee Characteristics

In addition to the exploration of offenders, it is also important to examine the characteristics of the arrestees associated with crimes in schools. Though 211,809 offender reports for the 5-year study period were such that age, gender, race, and number of offenders were not reported, some or all of these characteristics were available for 181,468 persons arrested for offenses that occurred at schools. (See Table 2.)

Table 10 shows the offense for which the arrestee was apprehended. The most common offense code reported in arrestee records was simple assault–a crime against persons, followed by drug/narcotic violations–a crime against society. These two arrest offense codes were reportedly associated with more than half (52.2 percent) of the total arrestees. Destruction/damage/vandalism of property accounted for a relatively small portion of arrestees (6.6 percent). All other larceny and burglary, both crimes against property, involved 5.8 and 5.0 percent of the arrestees, respectively. Each of the remaining arrest offense codes accounted for less than 5.0 percent of the arrestees. Note that the arrest code does not necessarily match any of the offense codes in an offense segment in the same incident.

Table 10: Arrestees of Crime in Schools, by Offense, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Offense | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| Crimes Against Persons: |

||||||

|

Simple Assault

|

6,436 | 9,136 | 10,120 | 11,550 | 14,220 | 51,462 |

|

Intimidation

|

830 | 1,631 | 1,327 | 1,434 | 1,776 | 6,998 |

|

Aggravated Assault

|

1,009 | 1,228 | 1,291 | 1,427 | 1,531 | 6,486 |

|

Forcible Fondling

|

231 | 300 | 357 | 341 | 446 | 1,675 |

|

Kidnapping/Abduction

|

43 | 66 | 78 | 80 | 107 | 374 |

|

Forcible Rape

|

48 | 55 | 31 | 65 | 60 | 259 |

|

Sexual Assault With An Object

|

12 | 10 | 34 | 26 | 36 | 118 |

|

Forcible Sodomy

|

19 | 20 | 23 | 20 | 22 | 104 |

|

Statutory Rape

|

9 | 13 | 11 | 16 | 30 | 79 |

|

Murder and Nonnegligent Manslaughter

|

1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 27 |

|

Incest

|

0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 12 |

|

Negligent Manslaughter

|

0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Crimes Against Property: |

||||||

|

Destruction/Damage/Vandalism of Property

|

1,755 | 2,141 | 2,210 | 2,665 | 3,138 | 11,909 |

|

All Other Larceny

|

1,579 | 2,004 | 2,004 | 2,336 | 2,689 | 10,612 |

|

Burglary/Breaking and Entering

|

1,430 | 1,679 | 1,698 | 2,130 | 2,066 | 9,003 |

|

Theft From Building

|

1,188 | 1,387 | 1,440 | 1,845 | 1,973 | 7,833 |

|

Stolen Property Offenses

|

213 | 256 | 313 | 434 | 476 | 1,692 |

|

Arson

|

217 | 234 | 253 | 298 | 356 | 1,358 |

|

Theft From Motor Vehicle

|

183 | 205 | 208 | 288 | 274 | 1,158 |

|

Counterfeiting/Forgery

|

144 | 210 | 209 | 204 | 207 | 974 |

|

Shoplifting

|

124 | 176 | 165 | 165 | 217 | 847 |

|

Motor Vehicle Theft

|

144 | 136 | 182 | 195 | 166 | 823 |

|

Robbery

|

104 | 144 | 163 | 200 | 191 | 802 |

|

False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game

|

59 | 90 | 155 | 85 | 116 | 505 |

|

Impersonation

|

52 | 71 | 120 | 67 | 124 | 434 |

|

Theft From Coin-Operated Machine or Device

|

71 | 101 | 80 | 54 | 87 | 393 |

|

Theft of Motor Vehicle Parts or Accessories

|

58 | 79 | 56 | 73 | 65 | 331 |

|

Credit Card/Automatic Teller Machine Fraud

|

38 | 47 | 42 | 51 | 43 | 221 |

|

Embezzlement

|

29 | 41 | 37 | 62 | 45 | 214 |

|

Pocket-Picking

|

33 | 30 | 36 | 33 | 38 | 170 |

|

Purse-Snatching

|

18 | 25 | 22 | 38 | 41 | 144 |

|

Extortion/Blackmail

|

15 | 32 | 22 | 12 | 29 | 110 |

|

Wire Fraud

|

2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 19 |

|

Bad Checks

|

0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

|

Bribery

|

1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Crimes Against Society: |

||||||

|

Drug/Narcotic Violations

|

5,819 | 7,860 | 7,850 | 9,949 | 11,816 | 43,294 |

|

Weapon Law Violations

|

1,219 | 1,625 | 1,510 | 1,872 | 2,297 | 8,523 |

|

Drug Equipment Violations

|

717 | 1,030 | 967 | 1,123 | 1,271 | 5,108 |

|

Disorderly Conduct

|

194 | 496 | 557 | 751 | 947 | 2,945 |

|

Trespass of Real Property

|

79 | 121 | 118 | 192 | 186 | 696 |

|

Liquor Law Violations

|

82 | 123 | 74 | 158 | 157 | 594 |

|

Drunkenness

|

24 | 28 | 50 | 46 | 54 | 202 |

|

Pornography/Obscene Material

|

20 | 34 | 49 | 16 | 36 | 155 |

|

Driving Under the Influence

|

9 | 16 | 18 | 27 | 25 | 95 |

|

Curfew/Loitering/Vagrancy Violations

|

15 | 10 | 25 | 30 | 14 | 94 |

|

Betting/Wagering

|

2 | 2 | 13 | 19 | 19 | 55 |

|

Prostitution

|

2 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 22 |

|

Operating/Promoting/Assisting Gambling

|

0 | 12 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 19 |

|

Gambling Equipment Violations

|

0 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 19 |

|

Family Offenses, Nonviolent

|

0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 18 |

|

Assisting or Promoting Prostitution

|

0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Crimes Against Persons, Property, and Society: | ||||||

|

All Other Offenses

|

358 | 330 | 410 | 621 | 674 | 2,393 |

| Non-Crime: | ||||||

|

Runaway

|

27 | 19 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 63 |

|

Total Persons Arrested

|

33,280 | 34,360 | 41,057 | 48,109 | 181,468 | |

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

The largest group of arrestees about whom the age23 was known (41.8 percent) was 13 to 15 year olds. Arrestees who were 16 to 18 years old accounted for 32.7 percent; 19 or older, 14.2 percent; 10 to 12 years old, 10.2 percent; and 5 to 9 years old, 1.1 percent. Twelve arrestees who committed crimes at schools were reportedly age 4 or under.24 For those arrestees about whom the age was known, arrestees were 6.0 times more likely to be 18 years of age or younger than to be 19 years of age or older. The age was unknown for 171 of the arrestees. (Based on Table 11.)

Table 11: Arrestees of Crime in Schools, by Age1, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Age (Years) | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| 0–4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 12 |

| 5–9 | 358 | 472 | 410 | 376 | 412 | 2,028 |

| 10–12 | 2,494 | 3,539 | 3,607 | 4,093 | 4,672 | 18,405 |

| 13–15 | 10,138 | 13,960 | 14,351 | 17,107 | 20,266 | 75,822 |

| 16–18 | 7,863 | 10,609 | 10,987 | 13,726 | 16,052 | 59,237 |

| 19 or Older | 3,770 | 4,644 | 4,980 | 5,726 | 6,673 | 25,793 |

| Unknown Age | 37 | 53 | 25 | 26 | 30 | 171 |

| Total Arrestees | 24,662 | 33,280 | 34,360 | 41,057 | 48,109 | 181,468 |

1Law enforcement may report a range of ages. NIBRS reports the midpoint of the age range (e.g., offender age 25-35 is reported as 30).

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

During the 5-year period, 78.2 percent of the 181,468 arrestees were males, who were 3.6 times more likely to be arrested than females. (Based on Table 12.)

Table 12: Arrestees of Crime in Schools, by Gender, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Gender | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| Male | 19,717 | 26,343 | 26,812 | 32,146 | 36,868 | 141,886 |

| Female | 4,945 | 6,937 | 7,548 | 8,911 | 11,241 | 39,582 |

| Total Arrestees | 24,662 | 33,280 | 34,360 | 41,057 | 48,109 | 181,468 |

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

Of the 179,109 arrestees about whom the race was known, 72.8 percent were white; 25.3 percent were black; and 1.9 percent were all other race categories combined. White was 2.7 times more likely to be reported as the arrestee race than were any of the other race categories. A total of 2,359 arrestees were reported with an unknown race. (Based on Table 13.)

Table 13: Arrestees of Crime in Schools, by Race, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Race | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| White | 18,589 | 24,194 | 24,943 | 29,084 | 33,518 | 130,328 |

| Black | 5,308 | 8,032 | 8,274 | 10,663 | 13,077 | 45,354 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

277 | 410 | 383 | 523 | 521 | 2,114 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native |

171 | 232 | 289 | 268 | 353 | 1,313 |

| Unknown Race | 317 | 412 | 471 | 519 | 640 | 2,359 |

| Total Arrestees | 24,662 | 33,280 | 34,360 | 41,057 | 48,109 | 181,468 |

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

Law enforcement agencies submitting NIBRS data are not required to report the ethnicity of the arrestee to the FBI. Of the 136,957 arrestees about whom ethnicity was known and reported, 89.4 percent were non-Hispanic. Excluding unknown ethnicity, arrestees were 8.4 times more likely to be non-Hispanic. (Based on Table 14.) There were 18,208 arrestees about whom the ethnicity status was not reported during the 5-year study period.

Table 14: Arrestees1 of Crime in Schools, by Ethnicity, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Ethnicity | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| Hispanic | 1,729 | 2,439 | 2,862 | 3,439 | 4,103 | 14,572 |

| Non-Hispanic | 16,791 | 22,783 | 23,631 | 27,638 | 31,542 | 122,385 |

| Unknown Ethnicity | 3,793 | 4,440 | 4,631 | 5,820 | 7,619 | 26,303 |

| Total Arrestees1 | 22,313 | 29,662 | 31,124 | 36,897 | 43,264 | 163,260 |

1Over the 5-year study period, there were 18,208 arrestees for whom the ethnicity was not reported.

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

As with supplying the ethnicity of an arrestee, providing resident status for an arrestee is an optional reporting field in the NIBRS. For the purpose of this study, a resident is a person who maintains his/her permanent home for legal purposes in the locality (that is, town, city, or community) where the school is located and in which the crime occurred.25 Of the 145,339 arrestees about whom resident status was known and reported, 79.2 percent were residents. When the resident status was known, arrestees were nearly

3.8 times more likely to be residents of the community in which the crime took place. (Based on Table 15.) During the 5 years of data submissions from 2000 to 2004, there were 17,767 arrestees about whom resident status was not reported to the UCR Program.

Table 15: Arrestees1 of Crime in Schools, by Resident Status, by Year |

||||||

| Year of Incident | ||||||

| Resident Status | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 5-Year Total |

| Resident2 | 15,367 | 20,661 | 21,609 | 26,294 | 31,112 | 115,043 |

| Nonresident | 4,278 | 5,686 | 5,768 | 6,811 | 7,753 | 30,296 |

| Unknown Residence | 2,263 | 3,155 | 3,193 | 4,294 | 5,457 | 18,362 |

| Total Arrestees1 | 21,908 | 29,502 | 30,570 | 37,399 | 44,322 | 163,701 |

1Over the 5-year study period, there were 17,767 arrestees for whom the resident status was not reported.

2A resident is a person who maintains his/her permanent home for legal purposes in the locality (i.e., town, city, or community) where the crime took place.

Note: See the study text for specific data definitions, uses, and limitations.

Limitations

Studies that use NIBRS data have inherent limitations. First, when the NIBRS data show increases in crime over a period of years, it should not be assumed that the volume of criminal incidents in the Nation actually increased. As seen in Table 1, such apparent increases from year to year may well be the result of increases in the number of law enforcement agencies (1,934 more agencies over the 5-year period) reporting their UCR data via the NIBRS format. As the percentage of agencies participating in the UCR Program via the NIBRS increases and the NIBRS data become more representative of crime nationwide, data analysts will be better equipped to identify increases and decreases in crime that are due to actual changes in crime volume rather than to reporting. Furthermore, changes in proportions between groups should not be interpreted as an actual change in the Nation’s crime characteristics. It is possible that demographics of the new reporting agencies are influencing the proportion (e.g., should the data show a sharp increase in the percentage of one particular race of offender between two years). As more law enforcement agencies report via the NIBRS, analysts will be more confident that the demographic characteristics of the data can be considered nationally representative. It is expected that, eventually, the NIBRS data, combined with other exogenous datasets, will allow researchers to evaluate the effect of crime reduction policies in reducing crime. Another potential limitation is that the agencies that submit their UCR data via the NIBRS format are not, for the most part, in large metropolitan areas. In spite of these limitations, there have been studies that suggest that the NIBRS data may be representative of the Nation’s crime (see, for example, Section V of Crime in the United States, 2002, “Bank Robbery in the United States”).

Another limitation of studies that use NIBRS data stems from the restricting level of disaggregation possible when using NIBRS location codes. For example, crimes committed at school, college, and university locations are all combined into a single NIBRS location code. Separating elementary and secondary schools from colleges is difficult, if not impossible, in the NIBRS format. The parameters available in NIBRS that might help distinguish whether an incident took place at an elementary school, secondary school, or college are not mutually exclusive to any group. For example, there are many 17 year olds in college and, conversely, many 18 year olds in high school during the same period of time; therefore, age of victim, offender, or arrestee are not variables that can identify whether the incident occurred in an elementary school, secondary school, or college. In addition, neither the victim nor the offender necessarily attends the institution where the offense occurred.

Lastly, the validity of NIBRS data has not been tested; therefore, one should be cautious in the interpretation of surprising findings, e.g., twelve 0-4 year old arrestees. (See Table 11.) However, since one purpose of this study is to show the arrestee and offender information that can be gleaned from incidents involving crime in school locations reported via the NIBRS, data such as these are included in the study.

Because of these limitations, the findings discussed in the present study cannot be generalized to the Nation as a whole. Readers are advised to be cautious in applying the results of this study to other research.

Summary and Conclusions

In summary, this study, over the 5-year period, found that 3.3 percent of all incidents reported via NIBRS involved school locations. The number of crime in school-related incidents was highest in October. Offense records were also most likely to include the use of personal weapons (hands, fists, feet, etc.), while reports of the offender’s use of alcohol, computers, and/or drugs were minimal. Reported offenders of crime in schools were most likely 13-15 year old white males who the victims reportedly knew; however, there was nearly an equally large number of 16-18 year old reported offenders. More than half of the arrestees associated with crime at school locations were arrested for simple assault or drug/narcotic violations. Arrestees had similar characteristics to the reported offenders, most likely being reported as 13-15 year old white non-Hispanic males who were residents of the community of the school location where the incident was reported.

As a society, we are concerned by crime in schools and driven by the need for better data and analyses that can be used to develop protections for these institutions and the people who use their services. When more agencies use the NIBRS format to report UCR data, the data will allow for statistical estimations and tests.

Future studies using the rich NIBRS dataset may look at incident, offense, victim, and property characteristics; regional and rural/urban differences; as well as other socioeconomic and demographic considerations, such as:

- Comparisons to other crime in school databases such as the Department of Education or other agencies.

- NIBRS data validity (e.g., explaining the twelve 0-4 year old arrestees).

- Various victim, offender, or offense rates based on population.

Incident Characteristics

- Exceptional Clearances of crimes in schools.

- Crime in schools by region.

- Differences in crime in schools between urban vs. rural settings.

- Association of time of day to incidents.

- Month of incident (April as compared to others for “rampage” homicides like Columbine and Virginia Tech).Offense Characteristics

- Hate crime in schools.

- Attempted versus completed crimes.

- Type of criminal activity or gang information.

Victim Characteristics

- Victims by age, gender, and race.

- Types of victim injury in violence in schools.

- Age differences between victims and offenders.

- Incidents involving single victims and offenders.

Property Characteristics

- Type of property loss associated with incidents at schools.

- Description of property type involved.

- Value of property in crime in schools.

- Type and quantity of drugs.

By extracting relevant data elements from the NIBRS portion of the UCR databases, and by presenting percentages and odds ratios for characteristic differences among offenders and arrestees, this study sheds light on identifying the characteristics of offenders and arrestees of crimes at schools. Statistics presented here do not identify the factors of crime in schools. However, the study is an example of the way in which the NIBRS data can be used to explore facets of seemingly difficult problems and to generate questions and further research. This study adds to the body of research concerning crime in schools and particularly the often overlooked categories of school-related property and society crimes. One aim of school officials and law enforcement is to reduce crime in schools in general. As such, the findings presented here may be useful for those officials and policy makers at educational institutions who are seeking to develop proactive policies, an important need to effectively protect these vital societal foundations.

Appendix B: Weapon (continued) |

|||||||||

| Offense | Poison | Explosives | Fire/ Incendiary Device |

Drugs/ Narcotics |

Asphyxiation | Other | Unknown | None | |

| Simple Assault | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7,899 | 4,039 | 11,661 | |

| Aggravated Assault | 34 | 20 | 151 | 20 | 11 | 2,074 | 249 | 457 | |

| Forcible Fondling | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 273 | 267 | 1,786 | |

| Forcible Rape | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 50 | 93 | 511 | |

| Robbery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 72 | 255 | |

| Kidnapping/Abduction | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51 | 59 | 320 | |

| Sexual Assault With An Object |

0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 32 | 23 | 76 | |

| Forcible Sodomy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 31 | 155 | |

| Weapon Law Violations | 6 | 537 | 85 | 9 | 1 | 1,199 | 208 | 952 | |

| Extortion/Blackmail | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 18 | 6 | 87 | |

| Murder and Nonnegligent Manslaughter |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| Negligent Manslaughter | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Justifiable Homicide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 40 | 561 | 236 | 41 | 14 | 11,683 | 5,051 | 16,260 | |

| Table | Data Used | Construction |

| 1 | US Census and UCR | - |

| 2 | NIBRS Administrative, Offense, Offender, and Arrestee Segments |

ORI and incident numbers were selected in the offense segment where offense location = “school/college.” These ORI and incident numbers act as unique identifiers and were matched to the other segments in order to count the selected table fields. The numbers reflect the number of records for each category. |

| 3 | NIBRS Offender Segment | Offender ages were collapsed into the given age groups. Each number reflects the number of offenders reported. Offenders were only counted once in the table. |

| 4 | NIBRS Offender Segment | Offender genders are selected by NIBRS gender code. Offenders were only counted once in the table. |

| 5 | NIBRS Offender Segment | Offender races are selected by NIBRS race code. Offenders were only counted once in the table. |

| 6 |

NIBRS Victim Segment | Victim-to-offender relationships are determined by victim segment data elements.NIBRS collects relationship information for up to 10 offenders for each victim. The numbers reflected indicate the number of relationships (not just the number of victims or offenders). For example, an incident with 3 victims and 3 offenders involves 6 people but 9 relationships. |

| 7 | NIBRS Administrative Segment | The numbers in the table are the number of incidents and report dates associated with school locations by month and year. On some occasions, the date of the incident is unknown to law enforcement. For example, a school principal notices vandalism at the school on Monday morning and reports the crime. Though the principal knows the vandalism did not occur before Friday afternoon, neither he nor law enforcement can determine whether it happened Friday evening, Saturday, Sunday, or early Monday morning. Therefore, law enforcement reports the earliest date in which the incident could have occurred (Friday) as the date of the incident. In other instances, a crime occurs during a holiday or summer break and is not discovered and reported until the start of school or after the change of a month. Law enforcement enters the date of the report as the date of the incident, potentially counting the incident in a different month than when it occurred. In this study, incidents in which the dates of reports were used accounted for 19.5 percent of the incidents reported as having occurred in school locations. However, the percentages by month for the dates of reports and the actual dates of incidents are very similar (within 0.5 percent for each month), which indicates that only a small percentage of incidents may have occurred in prior months. |

| 8 | NIBRS Offense Segment | The numbers in the table count the various entries reported for type weapon/force involved within an incident. Though each offense may have up to three types, the table does not count the number of weapons. For example, if three shotguns were used in an incident, the reporting officer records one weapon/force used type for shotgun. In addition, offense records with multiple weapon/force involved types are counted more than once in the table. |

| 9 | NIBRS Offense Segment | This table shows the number of offense records reporting the use of alcohol, computer equipment, and/or drugs by any of the offenders. As offenders may have used more than one type in an offense, the table does not reflect a count of offenders. |

| 10 | NIBRS Arrestee Segment | Numbers in the table count the number of arrestees based on the UCR Arrest Offense Code found in the arrestee segment. Each arrestee is counted only once in the table. |

| 11 | NIBRS Arrestee Segment | Arrestee ages were collapsed into groups. The table numbers equal the total number of arrestees reported. Each arrestee is counted only once in the table. |

| 12 | NIBRS Arrestee Segment | The table numbers equal the total number of arrestees as reported by gender. Each arrestee is counted only once in the table. |

| 13 | NIBRS Arrestee Segment | The table numbers equal the total number of arrestees as reported by race. Each arrestee is counted only once in the table. |

| 14 | NIBRS Arrestee Segment | The table numbers equal the total number of arrestees as reported by ethnicity. Each arrestee is counted only once in the table. Arrestee ethnicity is an optional NIBRS field. |

| 15 | NIBRS Arrestee Segment | The table numbers equal the total number of arrestees as reported by resident status. Each arrestee is counted only once in the table. Arrestee resident status is an optional NIBRS field. |

| A |

NIBRS Offense and Victim Segments |

The table counts the number of offenses for each offense type by year. Crimes against persons count one offense for each victim which is determined by the victim segment Victim Connected to UCR Offense Code(s) data element and can link up to 10 offense codes to the victim. Both crimes against property and society count only one offense per distinct operation which is determined by the offense segment. |

| B | NIBRS Offense Segment | This table has a unique unit of count. It is the number of weapon types found in offense records. Therefore, the table can be read as “there were 86,312 personal weapon types associated with simple assault offense records.” However, it can also be read as “there were 86,312 simple assault records associated with personal weapons.” This table does not count one offense for each victim of crimes against persons and only includes offense types for which weapon type is collected. |

Endnotes

1National Center for Education Statistics, “Public Elementary and Secondary Students, Staff, Schools, and School Districts: School Year 2002-03 E.D. TAB,” NCES 2005-314, US Department of Education, 2005.

2School Violence Resource Center, “Weapons and Schools II Fact Sheet,” University of Arkansas System, June 2003.

3National Center for Education Statistics, “Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2004,” US Department of Education, 2004.

4National Institute of Justice, “Crime in the Schools: A Problem-Solving Approach” (Summary of a Presentation by Dennis Kenney, Police Executive Research Forum), August 1998.

5National Center for Education Statistics, “Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2005,” NCJ 210697, November 2005.

6H.R. 3344, S.1925, S.1930.

7National Center for Education Statistics, “Digest of Education Statistics 2003,” NCES 2005-025, US Department of Education, December 2004. (Numbers are for the 2001-02 school year.)

8Security On Campus, Inc. “Clery Act History,” n.d.<http://www.securityoncampus.org/schools/cleryact/cleryact.html>, accessed on 08/03/2007.

9NIBRS Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines, Federal Bureau of Investigation, August 2000.

10Technical note for those who wish to replicate the study: NIBRS Data Element #9–Location Type, Code 22–School/College (includes university).

11Technical note for those who wish to replicate the study: NIBRS Data Element #13–Weapon/Force Involved, Weapon Type Codes 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15, respectively.

12Please refer to NIBRS Volume 2: Data Submission Specifications, Federal Bureau of Investigation, May 1992, for more details on time-window submissions.

13The term known offender does not imply that the identity of the suspect is known, but only that a characteristic of the suspect has been identified, which distinguishes him/her from an unknown offender.

14Law enforcement may report a range of ages. NIBRS reports the midpoint of the age range (e.g., offender age 25-35 is reported as 30).

15UCR race reporting guidelines for NIBRS Data Element #39–Race (of offender) follow the minimally accepted standards established by OMB Directive 15. The NIBRS guidelines can be found in NIBRS Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines, Federal Bureau of Investigation, August 2000, p. 100.

16UCR Handbook, NIBRS Edition, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1992.

17These three items are collected jointly in the NIBRS. Refer to p. 38 of the UCR Handbook, NIBRS Edition, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1992, for a detailed explanation and examples of how these items could be used in the perpetration of a crime.

18NIBRS Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines, Federal Bureau of Investigation, August 2000, p. 69.

19Weapon types are only reported for murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, negligent homicide, justifiable homicide, kidnapping, forcible rape, forcible sodomy, sexual assault with an object, forcible fondling, robbery, aggravated assault, extortion, and weapon law violations. UCR Handbook, NIBRS Edition, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1992.

20Summing the gun categories will not yield the number of incidents with guns as there may be more than one gun type in an incident. For example, an incident may have involved the use of a rifle and a shotgun.

21The Other weapon type is an umbrella category that captures weapon types not reflected in the specific weapon type definitions.

22One or more of the offenders may have used the type indicated and one or more offenders may have used more than one type in the same offense. It should also be noted that if an offender used a type in an incident with multiple offenses, its use will be counted in the table more than once.

23Law enforcement may report a range of ages. NIBRS reports the midpoint of the age range (e.g., offender age 25-35 is reported as 30).

24These data were not tested for validity and are presented as they are found in the NIBRS database. Please see the Limitations section for more details.

25NIBRS Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines, Federal Bureau of Investigation, August 2000, p. 104.